Knorr was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, and was raised in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in the 1960s. She finished her education in Paris and later London, where she eventually settled. Knorr has taught, exhibited, and lectured internationally, including Tate Britain, Tate Modern, The University of Westminster, Goldsmiths, Harvard University, and The Art Institute of Chicago. She studied at the University of Westminster in the mid-1970s, exhibiting photography that addressed debates in cultural studies and film theory concerning the “politics of representation” practices that emerged during the late 1970s and early 1980s. She is currently Professor of Photography at the University for the Creative Arts in Farnham, Surrey.

Karen Knorr’s photographs are both beautiful and disruptive. At first glance, one can ask how such enchanting, natural creatures roam the interiors of some of the most luxurious and formal places throughout the world? Eventually, the viewer finds that Knorr’s suspension of disbelief and her integration of symbolic animals and unique buildings come following over three decades of exploring themes of culture, society, and architecture.

In her aesthetic and art practice evolution, she has created various photography projects that explore a fascinating array of subject matter. From ancient myths and folklore of antiquity to projects that deal with class relations in modern society or gender roles, Knorr explores themes that reflect the “established” but ultimately transient cultural practices which are the bedrock of society. As a contemporary photographer and conceptual artist, she creates layered images with technical expertise and a profound conceptual framework. And, much like her work, Knorr’s personal life, filled with multicultural experiences, reflects the voyages through civilizations, identities, and historical narratives that make her practice so engaging.

“During the 1960s, Conceptual artists shifted away from traditional art media and the making of art objects, and moved instead toward ideas and their documentation. Ignoring photography’s historical connections and past interactions with the fine arts, they enlisted it as a neutral record-keeper of ideas and performances… Soon, in a further twist, Conceptualists began to explore photography’s complicated relationship to the real.” – 100 Ideas that Changed Photography, Mary Warner Marien

Karen Knorr was born in Frankfurt Am Main, Germany, in 1954. Her parents were both involved in the American war effort overseas during World War II. Her father was a major, and her mother worked first as a volunteer for the Red Cross and later as a photojournalist covering the Nuremberg trials. Growing up, her nanny, Ingeborg Jurkurat, spoke to her in German while both of her parents were multilingual. In essence, Knorr’s childhood was immersed in different languages, speaking German, English, Spanish, and French from a young age. At the age of four, the family would move to San Juan, Puerto Rico, where Knorr would live the rest of her childhood years growing up surrounded by Puerto Rican culture.

“My identity has been formed by this layering of cross-cultural influences and by my relationship to the art and photography students that I have taught in different art schools, including Goldsmiths College and the University for the Creative Arts.” – Karen Knorr.

Punks

In the early 1970s, Karen Knorr graduated high school and moved to Paris to study fine arts at L’Atelier, a foundation course for entry to L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts and Arts Decoratifs. She would eventually move to London in the late 1990s and begin creating several photographic series that explored culture and society. In her first years in London, Knorr would use the camera to investigate visual symbolism and identifiers of British culture of the late 20th century. Her series Punks, co-created with photographer Oliver Richon, and Belgravia, explored two vastly different but concurrent segments of the British public. One, countercultural, brazen, and doggedly defiant of the status quo, while the other, established, upper class, and conservative, embraced the politics of Thatcherism of the time.

“Here I was, this Puerto Rican American, and I was trying to understand British culture. I did it through photography. That’s how I sort of figure it out… I wasn’t just interested in photography as a technical tool. I wanted to think through photography in some way, I guess.” – Karen Knorr.

Gentlemen

A few years after, Knorr creates Gentlemen. This series explores exclusive men’s social clubs around London, investigating the British upper-class and the nature of these environments during Britain’s involvement in the Falklands war. Here, Knorr develops a dialogue with her aesthetic, using text along images to probe the discourse of the entrenched inner politics of the conservative sectors of British society.

“Karen’s work developed a critical and playful dialogue with documentary photography using different visual and textual strategies to explore her chosen subject matter that ranges from the family and lifestyle to the animal and its representation in the museum context.” – Karen Knorr website.

“My early work Gentlemen, I see, as a critique of patriarchal attitudes and conservative values that seem to be on the rise again.” – Karen Knorr.

Connoisseurs

In 1986, Karen Knorr began work on Connoisseurs, for the first time inserting various elements, like objects, people, or animals, into the pristine architectural interiors of prestigious buildings like The Victoria and Albert Museum or the Chiswick House. Knorr investigates heritage and authenticity by calling into question the cultural currency these renowned and historic places emit and what their importance says about British society. Knorr remarks that museums like these often dedicate rooms to housing “souvenirs” from locations worldwide, which the artist finds of particular interest. Knorr states: “Today’s connoisseur is yesterday’s man of taste.” Karen Knorr’s continued use of text, using words as a conceptual component, explores “connoisseurship.” She debates accepted ideas of beauty and taste in British high culture, a technique she continues to use in her art practice today.

“The use of text and captioning appeared as a device to slow down consumption of the image to comment on the received ideas of fine art in museum culture. These strategies still appear in her photography today with digital collages of animals, objects, and social actors in museums and architecture challenging the authority and power of heritage sites in Europe and more recently in India.” – Karen Knorr website.

Fables

Fables, Knorr’s series that started in 2004, marks a turning point in the photographer’s already storied career. Knorr uses analog and digital photography to create a series that mixes large format photography with digital post-production manipulation. For this series, Knorr combines some of history’s well-known fables from great writers like the Greek Aesop, the Roman poet Ovid, and Jean de la Fontaine, the 17th-century French poet. These ancient stories are then intertwined with references to contemporary pop culture, like tales from the massively successful commercial Disney movies.

“Play, humour, and irony are part of my work since Belgravia. I am also implicated in the irony and humour and do not stand above looking down, but I am very much part of the problems and issues referred to in my work… The making of the work which uses composite elements such as animals, for example, is a long and slow process initially that then moves faster when I have found the appropriate visual language to allude to the histories and stories that underpin the heritage.” – Karen Knorr.

India Songs

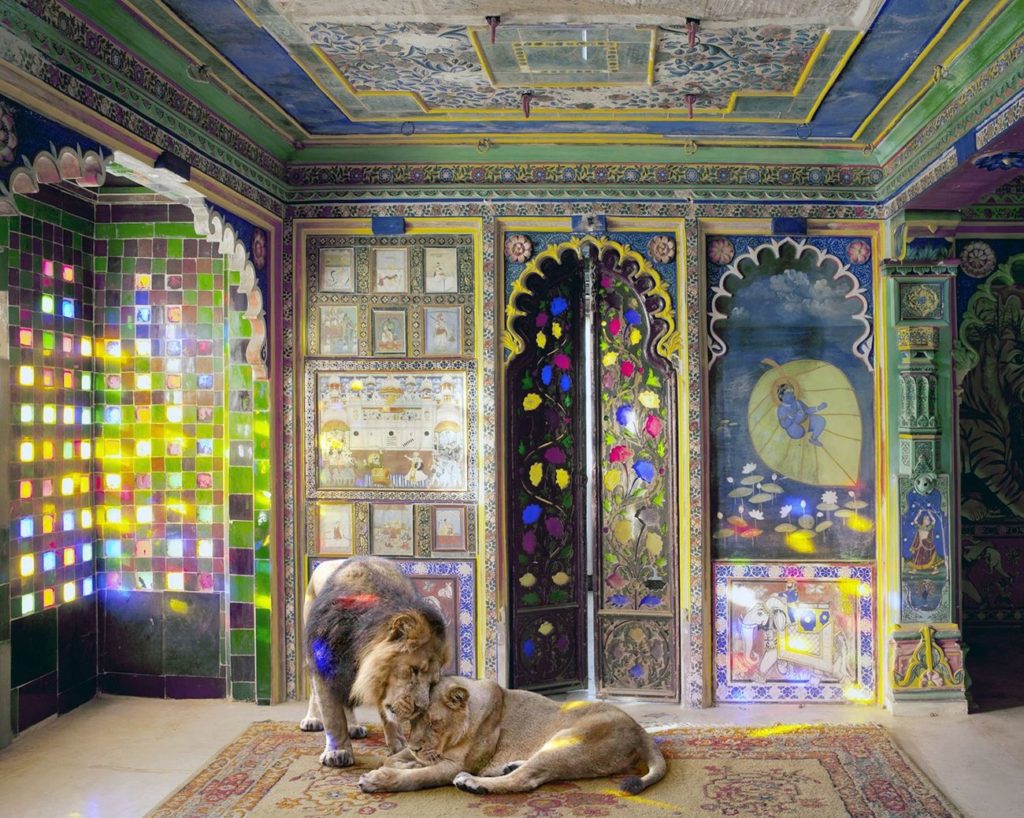

In 2008, Karen Knorr experienced a life-changing journey by traveling to India. With her series India Song, the artist explored the rich history of Rajput and Mughal cultural heritage. She investigates the power dynamics of gender roles, specifically those reserved to spaces for each gender. Using the tools garnered throughout her career of technical expertise and critical discourse, the artist marks a distinctive aesthetic feature as she continues to insert live animals into the sacred spaces of culturally significant architecture.

“Karen Knorr celebrates the rich visual culture, the foundation myths and stories of northern India, focusing on Rajasthan and using sacred and secular sites to consider caste, femininity and its relationship to the animal world. Interiors are painstakingly photographed with a large format Sinar P3 analogue camera and scanned to very high resolution. Live animals are inserted into the architectural sites, fusing high-resolution digital with analogue photography. Animals photographed in sanctuaries, zoos and cities inhabit palaces, mausoleums, temples, and holy sites, interrogating Indian cultural heritage and rigid hierarchies. Cranes, zebus, langurs, tigers, and elephants mutate from princely pets to avatars of past feminine historic characters, blurring boundaries between reality and illusion and reinventing the Panchatantra for the 21st century.” – Karen Knorr website.

Monogatari

One of Karen Knorr’s most recent and accomplished series is her work in Japan with the Monogatari series. Here, Knorr “imagines animal life and Japanese cultural heritage referencing Buddhist Jataka tales and Japanese stories.” She delves into Japanese culture by exploring sacred shrines and temples as well as ryokans (traditional Japanese Inn) and gardens.

“Knorr takes objects from the outside and places them in a series of incongruous situations; she infiltrates the stasis of the museum with animals that symbolize the unpredictable power of nature, primitive sexuality, the passing of time, and death are also implicit. The final perfect complete photographic prints are a result of Knorr’s ‘restorative’ playful, creative process and intense craft, workmanship and labour or ‘reparation’ as in the theories of Klein, Segal, and Stokes.” – Kathy Kubicki, The Photographic Practice of Karen Knorr.

In her body of work, Knorr compounds her skills at building complex images that create non-sequiturs where one has to step outside the picture to “read” a higher meaning within them. The photographs act as statements questioning our notions of social control and free will. The backdrops work as high culture settings that are often codified and come with accepted social behaviors. They are places redolent with civilization. The animals that are somewhat mysteriously placed within these confines cannot logically be nurtured in these spaces. The animals selected, be it a lion, a monkey, a swan, or a peacock, are culturally symbolic and anthropomorphic. They generally represent our unbridled free will to act without social constraints and cultural limitations. The viewer needs to ponder how these two divergent concepts can be brought together or if this is a possibility when one reflects on the work. Knorr’s photographs are visually seductive and offer the viewer aspects of the universe of totally different concepts of civilization and the potential and richness of the natural world.