Expanding the Language of Modernist Photography

André Kertész was a key figure in expanding the language of modernist photography. He intuitively captured the poetry of modern urban life with its quiet, often overlooked incidents and comic, occasionally bizarre juxtapositions.

His original use of the camera and unique way of looking at the world underscored life’s beautiful details. Later he pioneered the use of 35mm Leica point-and-shoot cameras and the recording of spontaneous moments in life. The native Hungarian was originally a stockbroker and would first develop his interest in photography around World War I when he served in the Austro-Hungarian army. He was wounded in 1915 and began to explore photographing active and physically fit people such as in his photograph “Underwater Swimmer, Esztergom”.

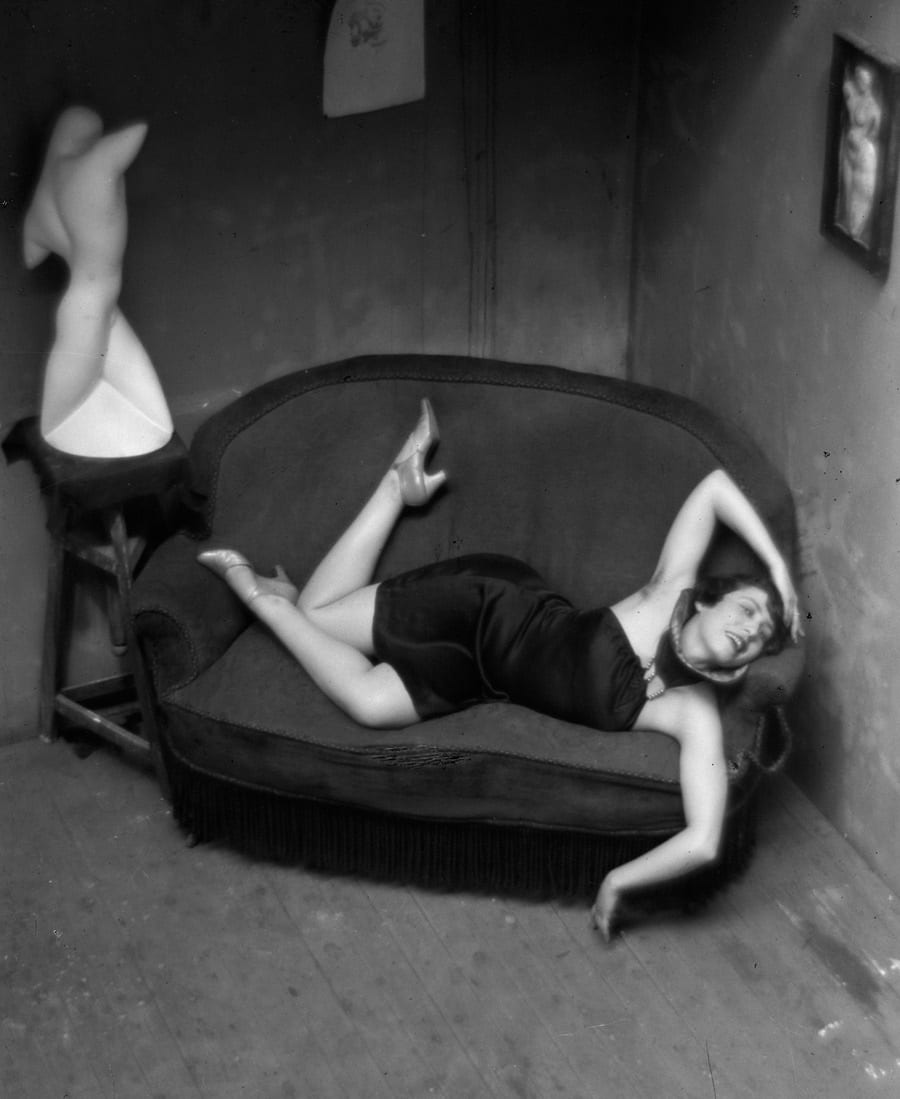

Satiric Dancer

By 1925, Kertész had arrived in Paris which was a magnet for aspiring artists such as Piet Mondrian and Constantin Brancusi who Kertész would befriend. István Beöthy was a fellow Hungarian émigré and a sculptor who would also fall into the same avant-garde circle as Kertész who all connected to the “new spirit.” It was in Beöthy’s studio where Kertész took the now iconic image, “Satiric Dancer” in 1926. The playful woman in the image is Magda Förstner. She was a Hungarian cabaret dancer and aspiring actress that Kertész had invited to the studio specifically for the shoot. Kertész recounted the situation decades later:

“I said to her, ‘Do something with the spirit of the studio corner,’ and she started to move on the sofa. She just made a movement. I took only two photographs…People in motion are wonderful to photograph. No need to shoot a hundred rolls like people do today. It means catching the right moment. The moment when something changes into something else.”

Förstner attempts to mirror Beöthy’s sculpture and her white limbs seem to represent the missing parts of the sculpture. The divan appears almost as a kind of sculpture pedestal. A framed image of a female nude sculpture also hangs on the wall to the right. Together with the torso sculpture opposite and Förstner herself, they form a triangle. The trio of components all related to the human form gives the composition a dynamic visual energy. It further suggests the energetic nature of Beöthy’s art while also embodying the jazzy exuberance of Paris in the 1920s. Förstner appears to be enjoying herself and there is a sense of spontaneous fun. This was a common theme in Kertész’s images combined with a developed sense of modernist form.

A Timeless Image

The image, designed to capture the “new spirit” now seems timeless in its appeal. It is heralded as one of the most successful and imaginative integrations of sculptural form, portraiture, and dynamic movement within the two-dimensional framework of the viewfinder. Henri Cartier-Bresson would later say about the photographer,

“Whatever we have done, Kertész did first. We all owe something to Kertész,”

From Paris to New York

André Kertész worked in Paris and captured additional “Chez Mondrian” and “Melancholic Tulip”. Amidst the growing political turmoil in Europe of the 1930s, Andre Kertész with his wife Elizabeth decided to take an offer to move to the U.S. and work for the Keystone Agency. Though Kertész struggled to find the same majestic romanticism of Paris in New York, his body of work continued to grow with images such as “Homing Ship”. Near the end of Kertész’s life, John Sarkowski; then acting director of photography at MoMA discovered his fantastic body of work and gave him a full retrospective in 1968.