Transcription in progress

Luntz: I’m really happy to have all of you here today. We send out these invitations, and on Saturday, we always wonder who’s going to show up. The whole staff here worked very hard on selecting and installing the work, as well as updating the website with the pieces. Jaye and I collaborated on the press release, so if you’re curious about Christopher Bucklow’s or Garry Fabian Miller’s work, the press release is a good resource. It provides some solid information about their artistic approaches.

You’re dealing with two photographers who aren’t classic photographers in the traditional sense of capturing recognizable scenes. They use their own inventive methods, working with film emulsion and other self-developed techniques. For the last 20-30 years, their focus has been on light as both the subject and the medium, which is very unusual and distinctive.

Christopher Bucklow’s journey to this point—creating the Guest pictures and the Tetrarch series over the last three decades—has been remarkable. It’s a story of healing and self-discovery. Fortunately, he’s here with us today, and I want to warmly welcome him. Personally, I feel incredibly lucky to have Christopher’s work here and to have spent the last few days with him.

Ever since I saw his work 15-20 years ago at Paul Kasmin Gallery, it has resonated deeply with me. His style, like Garry Fabian Miller’s, is so distinct that you can recognize it immediately. You don’t need to search for a signature—it’s unmistakable. Both artists have developed unique mediums over time that no one else uses, making their work truly one of a kind.

To present the two of them together is a special experience. They’ve been shown together often, they know each other well, and they’re good friends. While Garry is not traveling at the moment, Christopher made the journey here from outside London. I’m thrilled that he’s here and able to speak with us directly about his work.

We have clips from a feature film about Christopher, which is about an hour long, and we can send you the link if you’re interested. However, we thought it would be a missed opportunity not to have him engage with you live. He’s here in person to answer your questions and share his thoughts on the work.

Without further ado, I’ll hand it over to Christopher.

Introduction and Travel

Bucklow: Thank you very much, Holden. I am delighted to be here. I’m very happy that I got on that plane, flew from London to Miami, and then took the Tri-Rail train to get up here. It’s fantastic to be here—I’ve loved it. The view was great.

So, um, I’m probably going to stand up so I can see better.

Luntz: You can do whatever you like. The room is yours.

Bucklow: Thank you.

Starting with the Technical Process

Bucklow: So, I’m going to start by saying a little bit about what the pictures are, technically. Quite a few people want to begin there—that’s often the way into understanding what they are for many. I’ll explain the technique for a moment, and then, hopefully, we’ll get into some of the reasons why I invented it. But I’ll leave that part until after we’ve talked about what they are.

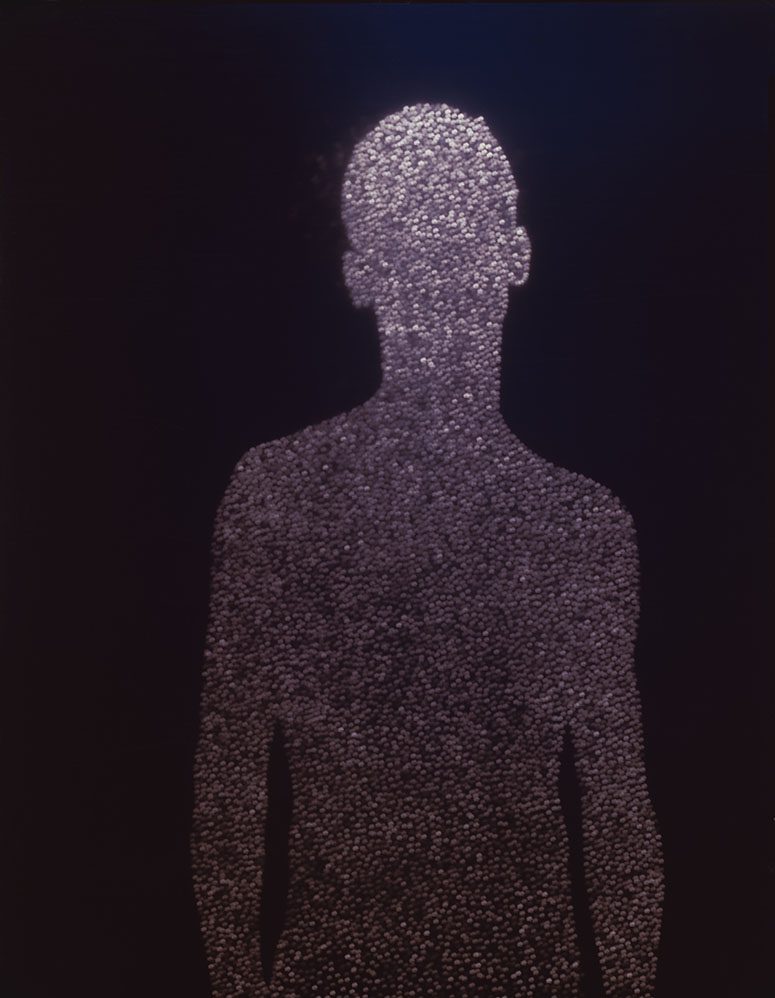

They are photographic. They involve pinhole photography, but instead of using a single aperture, I use many thousands of pinhole apertures. These apertures are arranged on the front of a very large camera. There’s no blowing up, no enlargement, and no negative. The sheet of paper that records the image sits inside the camera, at the bottom. If you’re familiar with the term “plate size,” it refers to the dimensions of that sheet of paper.

This camera takes a 40-inch by 60-inch plate size, meaning that’s the size of the paper sitting in the bottom of the camera. I magnetize the paper to hold it in place. The smaller camera, like the one used here, is 40 inches high by 30 inches wide. I also have a monster camera, which is 40 inches high by 100 inches wide—very panoramic.

Building the Cameras and the Process

Bucklow: Don’t picture these as fancy cameras. They are homemade wooden boxes. Honestly, they look like packing crates, but they are built to my exact specifications. I make them myself. The paper goes into the bottom of the box, and then a sheet of aluminum foil is placed on top. The foil is where all the pinholes—used to capture the photograph—are arranged.

I’ve specifically arranged the pinholes in the shape of the human figure. When I point the camera at the sky, each pinhole captures a small image of the sun. Some people mistake the dots in the image as pixels, as if it’s a form of digital photography. But this is the opposite of pixelated, electronic photography. This is, as I like to call it, dinosaur photography. It’s created with the most low-tech materials imaginable: a big box, a sheet of paper, and a bunch of pinholes.

The Exposure Process

Bucklow: To make an exposure, I point the camera at the sky and briefly pull a cloth off the top of the camera to let sunlight in. The exposure lasts only a fraction of a second. When people ask me how fast my camera is, I just say, “Quite fast, yeah.”

The Film and Visual Explanation

Bucklow: We also have a clip from the feature film about this process.

This is a documentary film that was shot this summer at my photography studio. There are a few brief segments that explain the process, and the visuals will help you understand it—which is the main thing.

The film is available on YouTube.

In this clip—while we’re sorting out the sound—I’m explaining how I developed the technique of using a multiple-aperture pinhole camera. It’s a counterintuitive idea because traditional pinhole photography uses just one pinhole. When I made my first pinhole camera, it had 100 pinholes. The cameras I use to create these photographs now have 25,000 pinholes. That means you’re seeing 25,000 images of the sun in these photographs.

Why 25,000 Pinholes?

Bucklow: People often ask, “Why 25,000? Did you count them?” Well, I did at the beginning. Now, I know that a typical human figure, with the way I arrange the spread and density of pinholes, results in around 25,000.

Why 25,000? It connects to the biblical lifespan: three score years and ten, or 70 years. If you add up the number of days in 70 years, it’s roughly 25,550. So, each of these figures contains a lifetime of suns.

The Origin of the Idea

The idea for the technique started when I was a kid—when I was about 13 or 14. I remember going for a walk with a friend, and the pavement was covered in little round, dancing light images. I said to her, “That’s odd because that’s obviously coming through the leaf canopy. But if you’ve got round leaves and you put them together, the holes between them are always angular—they’re always like triangles or squares or something. You can’t really explain how everything on the ground is circular.”

She went off to school the following day and asked her physics teacher, who said it’s because the tree is acting like a pinhole camera. That memory from when I was about 14 stuck in my mind for the next 15 years.

The Evolution of the Technique

Bucklow: There was a moment when I was planning to make some images of clusters of suns, like galaxies or something like that. I had been painting them. The painted versions were okay, but the beauty of the idea—the concept of this galaxy of light—wasn’t as powerful in paint as it was in my imagination. I wanted to make it more powerful, something that matched the depth of the emotion I felt about the image.

Early Experiments with Multiple Pinholes

Bucklow: I thought, “Okay, I’ll go to a camera shop where they have those throwaway cameras with little plastic lenses. I’ll go to their trash and take 100 of these plastic lenses, make a kind of dome of lenses, point it at the sky, and ‘Hey Presto,’ I’ll probably get a cluster of suns imaged by this technical dome of lenses.”

Then that plan seemed impractical. Suddenly, “ping!”—in the back of my mind, I thought, “A pinhole camera doesn’t only have to have one pinhole. What would happen if I had 10 pinholes? What would happen if I had 100 pinholes? What would happen if I had 25,000 pinholes?”

So I started to build the cameras and experiment.

The Cibachrome Paper and Process

Bucklow: And there was this wonderful paper—it’s now discontinued—called Cibachrome, as Holden mentioned. It’s a positive-positive paper. What that means is, when it sees something that’s red, it goes red; it doesn’t go the opposite color. There’s no negative. So, when it sees a blue sky, it goes blue, and this gives you this positive image.

Creating the Figures and Shapes

On this foil, I trace the outline of a silhouette—this is his shadow. Then, I use a blunt pencil to make a kind of heavy line over it, which impresses itself into the form. It’s just a normal household pin for the outline. After that, I very gently start creating varying apertures, making sure that some are large, going right through the full depth and width of the pin, while others are just nicking it.

Of course, the first time you make an exposure through one of these, it’s just an experiment to see where you messed up, basically.

Okay, so you can see there that the aluminum foil that goes on the front of the box is the same size as the sheet of paper. The figures are kind of one-to-one—the scale of the outline drawing of the silhouette and the amount of pinholes is exactly life-size. It’s one-to-one when it gets recorded.

The Final Steps of the Process

Bucklow: Okay, so we’re going to see the camera being rolled out of the studio. The camera comes out of the studio on wheels, and I take it into the field next to my studio. That’s where, if there’s any sunshine—and this is England, remember—we make an exposure.

To be in the quiet, utter darkness for all that time, loading the camera very methodically, and then to open that door into the blinding sunshine, wheel the camera out, and allow the Sun’s light into the camera just for that moment… Then, bring it back into the dark and spend another hour unloading it, making the paper safe, and getting it ready for development. The process is incredibly analog. It’s a sort of miracle that you get a clean image.

As you’ve seen, my studio is not a photographic studio. You have to allow for the conditions—it’s a barn, with owl feathers falling from the ceiling if you’re not careful.

The Hands-On Process of Capturing Light

Okay, so the camera’s been brought out of the darkroom where I’ve loaded the sheet of paper into it. The foil is on top, and there’s a sheet of cardboard over it as a baffle to stop any light from getting through the pinholes. The white sheet is just there to keep the camera cool on a sunny day.

The Role of the Black Cloth Shutter

So, this big black cloth is the shutter. If I expose that sheet of paper to all 25,000 Suns at once, it would turn white instantly—you wouldn’t get anything. So, in order to make the exposure, there’s a black cloth with a slit in it. There’s a piece of wood reinforcing the opening, and it’s about a centimeter (half an inch or so) wide. That gets pulled up the front of the camera very smoothly, and as it travels up the front of the camera, on top of the pinhole foils, it lets the light in.

The Uncertainty of Timing

This is why I’m never quite sure how long the exposure is—it depends on how quickly I pull it. Usually, I make a note in the notebook saying, “Sun quite bright, pulled the shutter quite quickly.” The next time I look, I think, “What was quite quickly?”

So, the shutter is going on, and you’ll see the shot of me pulling up the camera and making the exposure in a moment.

The Rustic Studio Experience

You can see it’s a pretty rural environment that these photographs are made in, and it’s kind of a miracle that there aren’t grass clippings or sheep over the images. It’s not a lab. My studio is not a lab; it’s more of a barn, as I said. I think we’re going to reboot.

Q&A During the Reboot

Audience member: Can I ask a question while you’re rebooting?

Bucklow: Yes, please.

Audience member: Why is it that you went all the way from the barn door out to where the sheep were? There must be some light consideration.

Bucklow: Yes, a pinhole lens, if you can call it a lens, is incredibly wide-angle. If I made an exposure close to the buildings around where they get recorded on the periphery of the camera. technically, you could shoot anything through this pinhole array. I set it up in a studio and put somebody sitting on a seat in front of it and zapped them with flash guns for 10 minutes, it would record 25,000 images of that person’s face. So, it’s the reason that they’re only little round circles. It is because it is photographing the Sun’s face, its disc, each time.

The Effort of One Exposure

Luntz: In this age of instant photography, you think, “Who does this to get one exposure?” You can’t make multiples.

Returning to the Darkroom

Bucklow: There you go. It’s done. Then I put the cardboard baffle back on it and roll it back. Let’s just roll it. Straight into the studio. So it’s heading back into the darkroom.

Bucklow: So we’ve just rolled the camera in after having made the exposure, and now we’re shutting the door and we’re going to be in the dark. I’m just going to take off the white cloth that kept the camera cool while we were outside. So this is the light baffle before we put the shutter on. It kept the light off while we were rolling it out. I’m going to take this off and then take the foil off that has the pinholes in it. All of that has to be done in pitch blackness, so— and that’s the same with loading it up. I’m going to be stripping off all this tape down here in order to be able to get the foil off.

Okay, so we’re going dark.

Revealing the Image

So, the paper’s now been developed, and we’re seeing the exposure that was made.

This is how it comes out of the developer. When I loaded it up, I put this sheet of paper into the camera. These silhouettes here—these photograms—are of magnets that magnetize the paper down to the bottom of the camera. That’s what keeps the paper flat in the bottom of the camera—these magnets.

So, would I make any adjustments to this foil? Might put another couple of brighter suns into there. Yeah, there’s not much wrong with it, is there?

Explaining the Sun Imagery

Bucklow: I don’t know if we’ve talked about this, but each of those pinholes images an image of the Sun. So, the pinhole on the foil that made this little Sun on the arm also saw the whole of the blue sky. And this little Sun, which made this image, also saw the whole of the blue sky.

You’re getting 25,000 blue skies layered on top of each other, and that’s why the blue is so intense. The width that a pinhole sees—the lens that a pinhole makes—is very, very wide-angle.

Bucklow: This is just a still slide. It’s to show you that the paper is very sensitive to light at noontime and during the middle of the day. But if you make an exposure at sunset, it can see the Sun—the Sun registers fine—but the sky itself is too dim, and the paper doesn’t register it.

So, although this is a sunny sunset, and the Suns are recorded fine, the paper has stayed dark. It almost looks like a nighttime picture with the Moon, but it’s not—those are Suns.

Bucklow: Each one, when photographed from my studio, shows the Sun setting into a forest about two or three miles away on another hillside. As the Sun goes down, it sets into the trees, and each one of these little Suns has a tree trunk in it if you look.

There you go. I guess I’m showing you this just to make it obvious that these are little discs of the Sun, not somehow some part of an image of the pinhole itself.

The Development Process

Audience member: How do you fix the image on that large paper?

Bucklow: When the exposure is made, I roll the camera back into the studio in the dark. I take the paper out, roll it up in a dark slide, and then I put it into a friend’s developing machine. It runs a Cibachrome developer—it’s the only one left in the UK now.

It’s in private hands and is no longer a commercial product. The paper goes through the development process and comes out as you saw it.

A Leap of Faith

So, when I first made these, this was in the early ’90s. At that point, my wife and I both quit our jobs. I was an art historian working at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and she worked for the BBC’s picture library.

That year, we got married, and these photographs started to become a reality in my life. I could see that the technique worked. With a leap of faith, we both decided to leave our jobs and move to Italy, to Venice.

A lot of the first images—and some of the ones included in the exhibition here—were made in Venice. This is just a little film about how I made them there.

Bucklow: By ’93, then, I’d asked my father to build me the big 10×8, an actual 30×40 dark slide, so I could start doing life-size figures. At that point, Sue and I both quit our jobs. Sue was working for what used to be the BBC Picture Library, and I was working at the V&A. We quit and moved to Venice as a romantic thing to do, and that move coincided with the beginning of the Guest series. That was the sort of leading cusp of where I was at that point, and so we transported the big cameras to Venice by ship.

We flew when we moved, so we had a few weeks while the stuff was arriving. We even took our furniture—it was crazy. One day, I got word that the barge was coming from the docks with the big cameras on it, driven by a fantastic old boatman called Gigi. He got to our canal, and we unloaded the big cameras. Then I spent almost two years making Guests in Venice, which was fantastic because of the atmosphere there—the golden light of the sunset on the lagoon.

Creating Guests

All the times of day created a variety of different colors with the Guests. It was bonkers because Venice is packed, so the best time of day to work was when everybody was having a siesta. I would get the cameras out of the studio and set them up on the canal side, outside the studio, if the sun was high. Obviously, with the buildings, you need the sun to be high in order to do it near the studio.

But if I wanted a low sun, which gives you a much richer, orangey Guest with a darker sky in it, then we would take the cameras to the lagoon side—the seafront, as it were. That involved carrying them up and down endless bridges over the canals. The locals used to think we were the mad English people toiling with this huge block of wood. Calling that thing a camera is slightly ennobling, isn’t it? It’s basically a packing crate with the solar foil on the top of it. Sue was helping me at the time, and we did it.

So, there we were in Venice, and Venice was perfect for getting different colors and different exposures at different times of day. There was a lot of mist on the lagoon, and we’re just going to show maybe 10 or so different colors and exposures.

The Colors

Bucklow: The colors are achieved like this: if it’s a blue Guest, if it’s a blue photograph, then that is just no filters—it’s just the sky. If it’s one of the darker ones, that is also unfiltered. But for any other color, I use some of those gels that the movie industry uses to change the lighting in a studio. I just put a strip of that color along the slit on that big black cloth.

Bucklow: So, in this instance, obviously it’s a green filter.

Luntz: Can you wait? But yeah, something Jaye thought was fascinating this morning—this is purple, right? You think it’s just a purple filter? No way. How did you make it?

Bucklow: Well, as Holden says, it’s kind of a bit like “suck it and see.” You don’t really know what the filtration is going to do, so you just put on certain filters and see what happens.

The purple filter, it turns out, works if you use a filter called “daylight to tungsten,” which converts blue light to a warmer light. It’s a kind of slightly orange filter. I thought a yellowy-orange filter seeing a blue sky would make green, but apparently, it just warms the blue up, so you get this lovely violet color.

Bucklow: This one, which is on the screen, is just the blue of a beautiful blue sky.

Bucklow: This one’s got a red filter on it.

Bucklow: Back to green again.

Bucklow: So this one is just a late afternoon shot where the paper couldn’t see the dim sunset sky but only recorded the setting suns.

Bucklow: This is the one in the gallery, actually, which is red.

Bucklow: Here’s the purple.

The Emotional Core of Guests

Luntz: Can you talk a little bit about where the Guests come from?

Bucklow: Okay, yes, when I began, I said I’d tell you about the technique because people are always curious about the technique. But I also said I’d try and refer to why I did them. I mean, we don’t often know where work comes from, I would guess, and it took me a long time to add up the evidence that was building up as I was making the series.

I was choosing people from my friendship group—some of them family, some friends—and I was just doing it from sheer joy. I mean, to make these things is a joyful act. Seeing them come out of the developer is a bit like being a ceramist. You dip a pot in the glaze, and you don’t know what’s going to happen. You put it in the kiln, open the door, and it’s either a wreck, a beautiful color, or disappointing. It’s like that with this kind of photography. You don’t know exactly what you’re going to get, especially since you have no idea what exposure you’ve got.

So, I’d assembled this group, which I’ve called the Guests, and after a few years, I started to think, “Huh, what links them all?” I realized they were my friendship group. Some people I was more comfortable with than others, and I started to feel the significance of the group as an emotional encounter with people. Then it clicked—oh my goodness, all these people I’ve chosen have been in a dream. I’ve dreamt of these people.

That realization made me think that if I was going to do more, they’d have to be people who had appeared in my dreams. I was also interested in dream analysis. I’m more of a Jungian than a Freudian, so I was intrigued by dreams from that perspective. It also connected with my former profession as a museum curator.

When I worked at the Victoria & Albert Museum, one of the things I became an expert in was the art of William Blake. He’s someone who also personifies inner entities, forces, and sub-personalities within his being. He represents them as a group of individuals who contest the inner spaces of his psyche. So, when you see a Blake painting, nearly everyone in it is a sub-personality contesting the psychic space within his mind, I guess.

So, that’s how the group was eventually constituted. As I say, it was unconscious at first, and then gradually, over the years, I suddenly realized this is what linked them.

Bucklow: So, the next slide is just an example to show you that the camera can be any size you like. This one is a building, and the face facing the sunset on the left is all aluminum. There’s a life-size figure in the middle of it there.

Bucklow: You can see that the size of the camera is now a small piece of architecture over there. As the sun moves overhead at noon and then sets in the west, it starts to shine through the pinhole silhouette on the west-facing aluminum wall. Inside, you get a live Guest image.

There was no intention to use photographic paper in this piece—it was just an experience where you could go in and be there with the figure. Of course, when the sun is high after noon, it shines through the pinholes onto the floor, so the figure is projected onto the floor. The piece is a bit like a clock, because as the sun goes down, the figure moves across the floor. As the sun continues to set, the figure begins to rise up the wall. Eventually, when the sun reaches the horizon at sunset, the figure stands tall on the wall.

I had no idea this would happen, but there was a moment when the figure was perfectly aligned with both the floor and the wall. It seemed to be standing on the floor, but because the pinhole array is high up on the wall, as the sun set further, the figure seemed to levitate off the ground and move up the wall. The first time I saw it was a moment of awe—it was silent, beautiful, and an unexpected accident.

Luntz: I mean, we’ve talked about this, but there are two important things to mention. First, the work by Christopher Bucklow, which was created during a very special event—the total eclipse. This location was the only place that experienced the total eclipse. The work was part of the Light and Earth project, which was highly sought after. Many people wanted to be involved in it, but only two individuals were chosen to build this project. Those two were James Turrell and Christopher Bucklow.

It’s important to note that the timing of this was very special, as it coincided with the total eclipse.

Bucklow: Yeah, in England, we don’t have total eclipses very often. This one happened in 1999, but the path of totality only clipped the very end of Cornwall, near very near to Land’s End—just a few square miles. You can imagine, half the population of Britain moved down to this tiny, tiny place to see the eclipse. It was cloudy. That’s England for you.

So, I’ll show you a little clip of what was inside the camera, inside the building. The image was projected onto, or projected itself, as it were, onto a cloth screen. As people moved around inside this thing, the cloth would blow in the wind. It was a very light kind of muslin, and so you got this lovely feeling of the figure blowing in the breeze.

Bucklow: But the breeze could blow through, and you get those brighter suns that seem nearer, while the less bright suns feel psychologically a little further away. There’s a kind of volume to the figures, but it’s not fully material. It’s as if the wind could blow through it. That sense, combined with the idea of it being lit from within, creates a likeness of being.

I’ll just show you another clip, which is talking about when I said in that little clip about the kind of lightness of being. This is introducing the idea of the metaphors that the work speaks. The fact that those figures, these figures, seem sort of material but sort of immaterial at the same time, and that there seems to be the possibility of movement of air through the figure as if it’s not a barrier to movement within and without.