Introduction

The artist that I’m introducing you guys to is Barry Salzman, and he’s come from South Africa to be here, so we’re really fortunate to have him here. Barry had a really different background as well. Barry first picked up a camera when he was 14 years old as a birthday gift, and he was living in South Africa at the time of the Apartheid, so South Africa was incredibly divided. It was completely segregated, and through his camera, he felt that he had more permission to go into different areas and document a part of South Africa that he really didn’t know otherwise.

After that, he went a practical route. He actually ended up in the United States, getting his MBA from Harvard and worked in the corporate world for many years. He’ll talk about it as well, but it just wasn’t as fulfilling to him. He was working as a managing director at Google and felt a call back to the arts. So, at 49 years old, Barry went back, he went to SVA, and studied photography, film, and mixed media, and he got his MFA at 51, not to give your age away.

So he actually went back to art, and what he does with his art and the way that he presents us with information is very topical right now and it’s really important work. But aesthetically, it’s also so incredibly beautiful and moving, and it’s really heavy subject matter that his work really kind of introduces us to. It’s talking about genocide and it’s talking about real atrocities that landscapes have experienced, but he’s showing how those landscapes have evolved over time and how the world does heal. And he wants everyone to be aware of what’s going on in the world and not kind of turn a blind eye to it.

Before I introduce you guys to Barry and let him take over, I have four questions that, while I was walking around the gallery the other night I was thinking about. We have a show for Barry, it’s called “Barry Salzman: How We See the World.” It opens on Saturday, so tomorrow, February 24th, and it’s open through March 23rd. And I would love it if you guys came, you guys are always welcome at both of our galleries. We’re right in Palm Beach on Worth Avenue. And if you come, please introduce yourself because I love meeting Dreyfoos students. I think it was the best educational experience I ever had, better than college, better than any other academic experience, was being here at Dreyfoos. And as I get older, I realize how important this community is.

So, the questions that I want you guys to think about as you’re looking at Barry’s work and hearing him speak are:

- What does the concept of bearing witness actually mean?

- Do we share collective responsibility for the actions of our fellow human beings?

- What are the inherent dangers of looking the other way or the cost of silence when you’re facing evil?

- And how does the landscape provide a visual link between the past and the present?

Barry is exhibiting in the United States for the first time. We are so happy to have him here, and before any of our clients, he’s come to speak to all of you guys. So please welcome him.

Hi there everybody. I feel like she should just do the whole speech. You can talk about the work as well as I can or even better. So I want to thank you all very much for coming and for having me here today.

When I was walking through the hallways, I was reminded of my time in high school and my involvement running the school photographic society. And that’s really when I fell in love with photography. And along the way, through my schooling as an adult, I’ve continued to go and hear artist talks at every opportunity. And many, many artists have inspired me along the way. I always, always wanted to be the kind of artist who inspired other students. So I thank you for the opportunity, I sincerely hope that I’m able to do for you what many have done for me.

I am very conscious that it’s Friday afternoon. If you’re anything like I was as a student, all you’re thinking about is the weekend. And here’s this guy, he’s going to make you focus on some pretty challenging subject material. So please stay with me. I will answer any questions you have afterwards.

So just a little bit of background. I had this absolute passion for photography. But when I was a kid, I had no idea that it could lead to a career path as an artist. In fact, the only photography I knew about as a kid was the guy who was the wedding photographer. And I knew that that was not what I wanted to do.

So for 30 years, I pursued a career which was super practical, but I didn’t love. I was not passionate about it and at the age of just before I turned 50, I figured if I didn’t really go back to art school and focus on it, the opportunity would go away as I got older. It was going to become harder, harder to have a serious second career. But it is an extraordinary thing to be able to say that your passion is in fact your career.

So I started, as Jaye said, as a young student during apartheid in South Africa. For those of you that don’t know, apartheid was sort of the governing regime of South Africa, where segregation between whites and non-whites was legally enforced. And to me, it just… I didn’t get it. It was upsetting. I didn’t understand it. But there was very strict censorship in South Africa. So there was no way to really get another point of view. We weren’t allowed to see points of view that were anti the government.

And my camera, in fact, gave me the permission to explore it, let me go into areas where white people weren’t allowed to go. And it let me sort of ask myself difficult questions. And I think a lot of photographers say the same thing, that the camera is their… I suppose their reason, their reason to explore. It gives you a way and dialogue and conversation that you may not otherwise be able to have. When I think about why I take photographs, it’s exactly for that reason. It’s to satisfy a curiosity. It’s to ask myself questions and to engage in the process of trying to answer those questions for myself. And I think you’ll see a little bit of what I mean when I show you the project we’re going to talk about today.

I do want to just share a piece of advice that was given to me that I found incredibly, incredibly helpful. It was my first day when I was doing my master’s. And the head of the program said to us, “When you make photographs, you have to be able to say something that hasn’t been said. Say something new.” And I thought, “I’m not nearly smart enough to do that. It’s difficult, particularly with the internet, right? Where every point of view is out there for the world to see.” And he went on to say, “If you can’t come up with something new to say, challenge yourself to try and say something about subjects that people know, but in a new way.” And that’s been the focus of my art practice. Everybody thinks they know about the Holocaust. Everyone thinks they understand genocide. And I felt so strongly about the subject that I wanted to find a new way to look at information that people think they know. So we’ll talk a little about that.

I do have a very intense, research-driven practice. I’m going to talk today about what works for me. But I want to be absolutely clear that every artist has their own practice. What works for me may not work for you. But over time, as you listen to artists talk, as you do your research, you’ll find the path that works for you. Mine is very, very research-driven. I’ll spend two years researching before I go and before I go and shoot. I’m very conscious of the other artists that I reference in my work, academics who’ve influenced me, and we’ll talk a little about some of those.

It Never Rained on Rhodes

So to kick off, I wanted to share with you just a two-minute clip from a video I did for my MFA thesis. My mother’s family was directly impacted by the Holocaust. And for my thesis, I wanted to start understanding my maternal heritage. And so I spoke to a lot of people who came from this little island in the Mediterranean called Rhodes Island, where Mom’s family was from. And in 1944, 1,673 people from that island were deported to Auschwitz. Six months later, only 150 were still alive when Auschwitz was liberated. So I’m going to show you a little clip and then we’ll go from there.

So in that work, every time someone said Auschwitz, Nazi, Hitler, Holocaust, I deleted those words out of it. I edited it out. If you know a little bit about European history, you can figure out what they’re talking about. But it was very important for me to abstract away from the particularity of the Holocaust and make this a broader message around loss—loss of heritage, loss of identity. It was interesting, the film—the full film is available on my website—it screened at a festival in New York, and the film just before me was about the loss of Black identity in Harlem. And when I was done, every one of the black people in the audience, all the African-American people in the audience, came up to me to thank me for telling their story of loss of place, loss of identity. And I think that’s sort of the crux of what I try to do with my work: to abstract from the particularity. Because if we’re too specific, I work completely opposite of documentary. I think when we’re very specific, we give the audience permission to disown responsibility. “That was then, but it would never happen now” or “That was there, but it would never happen here.” And that’s just not true. So that’s what this work was intended to do.

And when I would have audiences like this at film festivals, people would sort of say to me, almost with this Holocaust fatigue, like, “Barry, we know the story. Maybe we don’t know that lady, but we know the story.” And when we think we know the story, this is the kind of thing we’re used to seeing: it’s just a Google image search on Holocaust, and you see people dying, really thin people, skeletons. And it’s really about this sort of bleak loss. And I would say to people, if you think you know that story so well, help me understand why we collectively have said it at least 12 times since World War II. And everybody said, “Never again, never again.” We did it again and again and again. And similar themes are playing out right now. So it’s this idea of the recurrence that I became very interested in. If we know these stories so well, how do we explain repeating them again and again and again?

And so what I did is I decided there and then that I was never going to stop trying in my art practice to better understand these issues, and specifically to understand what it is about us collectively, as we bear witness, that enables perpetrators of these heinous crimes to continue to repeat them again and again and again. So I became interested in the idea of recurrence, as opposed to specifically the Holocaust or the genocide in Rwanda or in Bosnia. The idea of the recurrence was important to me. And also, as far as I know, no other artist had already dealt with this idea of recurrence, whereas many artists have dealt with each one of these separate genocides. So it was a way for me to try to have a different way to approach subject matter that people think they know.

So, the idea of that sort of became the anchor for the work you’re about to see: is the idea of this landscape as metaphor. You know, I think of this idea—the landscape as this metaphor for humanity—because like us, the landscape sees everything. Like us, it does nothing. It witnesses, but it doesn’t take action. And in fact, if you take the metaphor further, you can imagine the landscape almost becomes complicit in the recurrence because the trees shed their leaves, they cover up the evidence. But also very importantly, the landscape replenishes, it grows, it rejuvenates. And so for me, the metaphor is very beautiful because it is about our responsibility as witness, but it also talks about a hope for the future with regrowth, rejuvenation, rebirth. And so that’s what my work is all about.

I just wanted to point out here the importance of doing research. So there’s a Dutch painter called Armando, and he came up with this concept in his work that also deals with sort of the Holocaust. But he came up with this concept of the guilty forest, where he basically says the forest is guilty because it could see everything. And in fact, he goes further and he says the trees on the outside of the forest are more guilty than the trees on the inside because they could see more. So I just use that as an example because for me, the research I do into my work really drives my practice, and it was his writing about this idea of the guilty forest that led me to the idea of the landscape as metaphor.

It is, and you’ll see as we go along, it is super important for me to make what I think are beautiful pictures. So you’ll see that they’re all beautiful aesthetic photographs. But they deal a lot with this idea of the tension between good and evil, dark and light, beauty and horror. And I think that, for me, that’s what makes the work powerful. Generally, I don’t document specific sites where something terrible happened. I’m much more interested in the idea of bearing witness. So I’ll go to those specific locations, I’ll work with historians, genocide activists, archivists, to go to these specific locations, and then I’ll work backwards, like outwards from there, till I can find an angle to make what I think is an aesthetically pleasing picture. Because my view on this is the subject matter is difficult, right? People don’t really want to think about it, they don’t really want to have it in their homes. So if I can engage you on an aesthetic basis, if you just love the picture, then I think I have an opportunity to take that conversation further.

And when I first started working on this, people said to me, “You can’t do this. People don’t want to be reminded of this at home.” And I would say that that’s part of the problem. If it’s okay to have these conversations in the school or the museum or the university, but not in the home, we become part of the problem. So as you’ll see as we go through it, I make an enormous amount of effort to create images that people will like, that people will respond to before they even know what the work’s about.

So I did a Google search on the genocide in Rwanda, which was, for me, probably the most challenging genocide in history, where a million people were killed in 100 days, which is the fastest rate of killing in human history. And so when we think about it, this is the kind of thing we saw, much like what I showed you when I searched on Holocaust, right? Lots of skulls, bones, skeletons, big graveyards. We never think of this. And this is an example of my work.

Archival Glicée Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag

So one of the lessons that I learned at art school that I want to share with you is when you look at an artist’s work, the first thing you ask yourself is, “What’s the intent of the artist? What’s the artist trying to say?” And I want you to just look at that for a moment and think about it. So there are a couple of quite obvious things here, right? There are three photographs. This is a triptych. For those of you that don’t know, a triptych is a single piece of art made in three different pieces, but it forms one complete work of art. So there are some obvious questions here, right? Why are there three? Why is one in focus and then it gets blurred and then it gets more blurred? And what this one work sort of tells the story of my whole practice. The title of the work is “A Ravaged Land Healing,” and what I try to talk to there is sort of, normally, steady state, some turmoil, complete chaos. And the thing that I love about this work is you can switch the order around. You can put the first one third and the third one first, and people will always say, you know, “Why do you pick that order?” For me, I picked the order because I’m a little intuitive, but it does sort of ask the question, you know, what happens when you get here? Do we go back to a peaceful, normal existence? Do the chaos get worse? Does the cycle continue? And these are the sorts of things that I want people to think about.

So what I’m going to do is talk to you about the genocides that I’ve worked on, and I’m going to go through them in the order that I shot them, because you’ll see how my sort of thought process and my creative style has evolved. So there are, depending on what your sources are, there are at least a dozen genocides that have happened post-World War II and over 20 that occurred in the 20th century. I started on four. The first one was Namibia, which was in the very beginning of the 20th century, which, when you look at the Holocaust, many of you know about. Rwanda, I just talked about, and the very last one of the 20th century, and there will be more, sadly, was the genocide in Bosnia.

And it’s particularly upsetting because in 1994, a million people were killed in a 100 days, and the whole world, again, said “Never again, never again.” And a year later, right in the middle of Central Europe, we did it again, and the world turned a blind eye. So these are the four we’re going to talk about.

The Holocaust

The Holocaust was the first one I worked on. It was sort of an extension of my MFA thesis work that we talked about. And when you look at this work, the same as I said to you earlier, what’s the artist’s intent? So you look at that, the thing that’s immediately obvious is that it’s a series of grids. The next thing is one’s black and one’s white, or one’s very dark and one’s very, very light. So you sort of ask yourself, why? What’s Barry trying to say with this?

The grid structure is sort of a formal organizing structure that’s used quite a lot in contemporary photography, and it’s used for different reasons. I use it here because I want to talk to this idea of recurrence, of repetition. I want to try and bring some order to the chaos. But very importantly, in these works, you can see I’m moving my camera from left to right as I travel across the landscape. I made these works on the last mile of train track into a concentration camp, and it was this idea of sort of the last views of freedom the prisoners had as the landscape witnessed the prisoners going to their death. That’s sort of the metaphoric idea.

Obviously, I did these pictures many, many, many years after these terrible events happened. But when you take a photograph and you move left to right, our eye goes left to right. So if you’re moving left to right, I feel like you’re giving the audience permission to enter, and then you’ve lost the audience. So in order to stop that from happening, I tried to work with these grids. So your eye travels left to right, you go from here to here to here. So I’m keeping you in the image as opposed to a single image of left to right motion. You don’t stay in for very long. And I’ll point out the contrasting style in a moment. So that was just another example how I continue when working with horizontal movement. I continue to work in sequence so that we can keep the attention of the audience.

Another idea with grids is to show different facets of the same thing. So all of these pictures were done, obviously, you can see the same scene, but they’re slightly different angles of the same scene. And then this happened. So completely different, right? This is where I was before, and this was a week apart when I made these. And I want to tell you a little story about this picture because it’s the one photograph that really changed my direction as a photographer.

So I was in Poland, and I was working with historians who took me to sites of unmarked mass graves. And I was in this forest, and you could still see the mounds in the forest. Forty thousand people had been buried in shallow pits in that forest during the Holocaust. And the historian who was taking me around told me the story about how what would happen is the Nazis would march Jews to the outskirts of the village, line them up in front of shallow pits in the forest, and there would be one behind the other. The Nazis would shoot the one, they would stumble into the pit and then the next line of people would step forward and meet the same fate. They were stripped naked so no one had any way to defend themselves. And there was this man standing in line and in front of him he saw his two children get shot and he went crazy. Just, you can imagine the delirium, the complete torment of seeing that. And apparently he ran but there was no way he was getting away. He didn’t know his way out – up, down, left, right. And he ran in this crazed way through this forest, completely traumatized. And so I asked the team if they could leave me on my own in the forest for a little bit and I sat there for ages trying to imagine what that man had endured. I wanted to try and come up with a visual language, a way to show that story visually. So I put my camera on the tripod, put on a slow shutter speed and just bashed the camera around – left, right, up, down. You know, this idea of completely delirious trauma. And I must have shot, I don’t know, thousands of pictures and this was one of them that emerged.

It’s a little hard to see but in the background here, the leaves are incredibly sharp. You can see every single leaf and same with the floor. But you also have this idea of blur. It’s important for me to tell you that I make every photograph in one single exposure. I don’t use compositing, I don’t use multiple images, because I feel like my work talks about our ethical responsibility of bearing witness and I feel like, as the artist, if I’m commenting on the ethics of seeing, I have to have some ethical boundaries within the way I make a work. So for me, they are all made in a single exposure.

It’s an interesting technique for those of you who do photography to try. Where I put the camera on a tripod and for part of the exposure I keep the camera still, that’s how I’m getting the sharpness, and then just before the lens closes I’ll tilt the camera, or move it left to right, or up and down to get this idea of blurriness and focus. And what I’m trying to accomplish there is to create a visual language for the idea of the veils or the filters through which we view inconvenient history. And I think a lot about this idea of the small child who watches a scary movie through a gap in their fingers. Even a child knows that the movie hasn’t changed but by putting something in front of our vision, by obscuring our view, we give ourselves permission to be less afraid, less accountable, less responsible.

Rwanda

And so I did a whole series of works in this same style with some sharp, some blurred, moving the camera. A lot of this very sort of milky, veiled feeling. Almost to create this separation between evidence and witness.

This is one that I just love because it’s called “Defiant Blooms” and these really are just little weeds. But, despite everything, they prevail. They continue to flower. They look beautiful. They grow against all odds.

Another one. You can see here what I’m doing by moving the camera. All this white is really the sky. By dragging the camera, your sensor responds to highlights more than it does to shadow. So, I’m pulling essentially the light from the sky over the front of the image.

For me, a powerful picture because obviously with that beam of light in the middle, it talks about the hope in the darkness.

Again, like a super, super calming image that talks to this tension between the beauty of place and the trauma of what happened in that place.

The Day I Became Another Genocide Victim

And then you get completely caught by surprise sometimes, right? I told you, I spent two years researching. I plan methodically. I know exactly where I’m going. I work with historians and archivists. So, I was in Rwanda shooting the landscapes that you just saw. And while I was there, a news story broke. This was in 2018. A news story broke that a new mass grave had just been discovered from quite close to where I was doing my landscapes. This was now 24 years after the genocide, and they were still discovering mass graves.

So, I said to the team I was with, I wanted to go and see it. Not to shoot it, in the same way I went to see Auschwitz to educate myself, but I didn’t shoot there. But I wanted to go and see this place to inform my practice, to better understand what had happened on that land. And it was just the most extraordinarily upsetting experience.

They were bringing out kids’ clothing from the ground. The two volunteers I was with were in tears. They were from the Kali Genocide Memorial. They had both identified where their parents had been killed by the parents’ clothes that came out of a mass grave because the bodies were so badly mutilated. So, they were traumatized.

We were in tears, and it was really the first time, maybe ever, that I felt like as an artist, I couldn’t walk away. I couldn’t just take a few pictures with my phone; I had to do something.

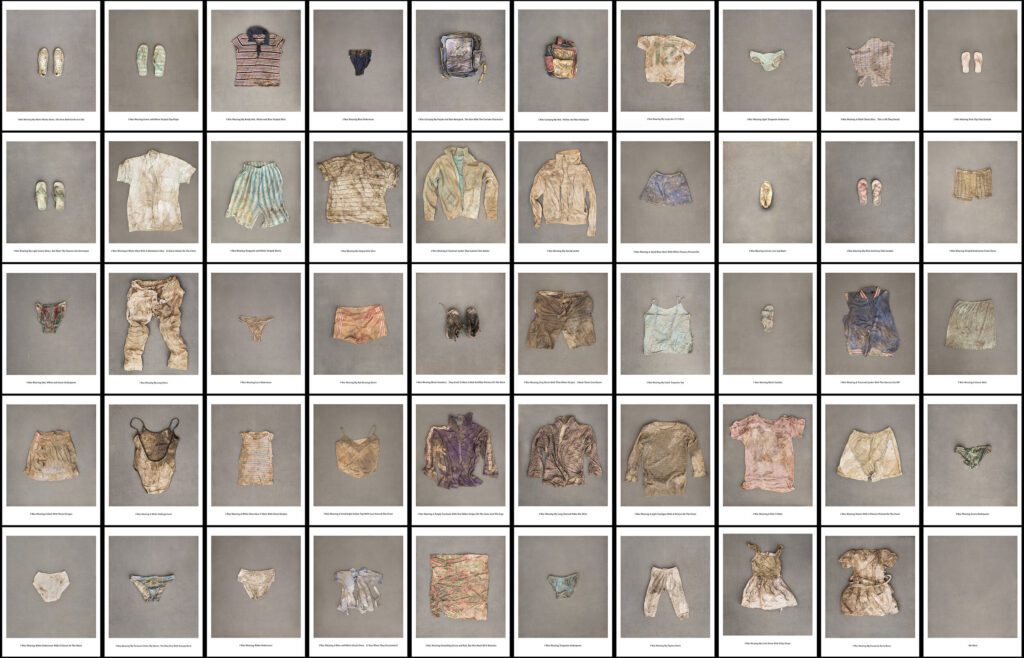

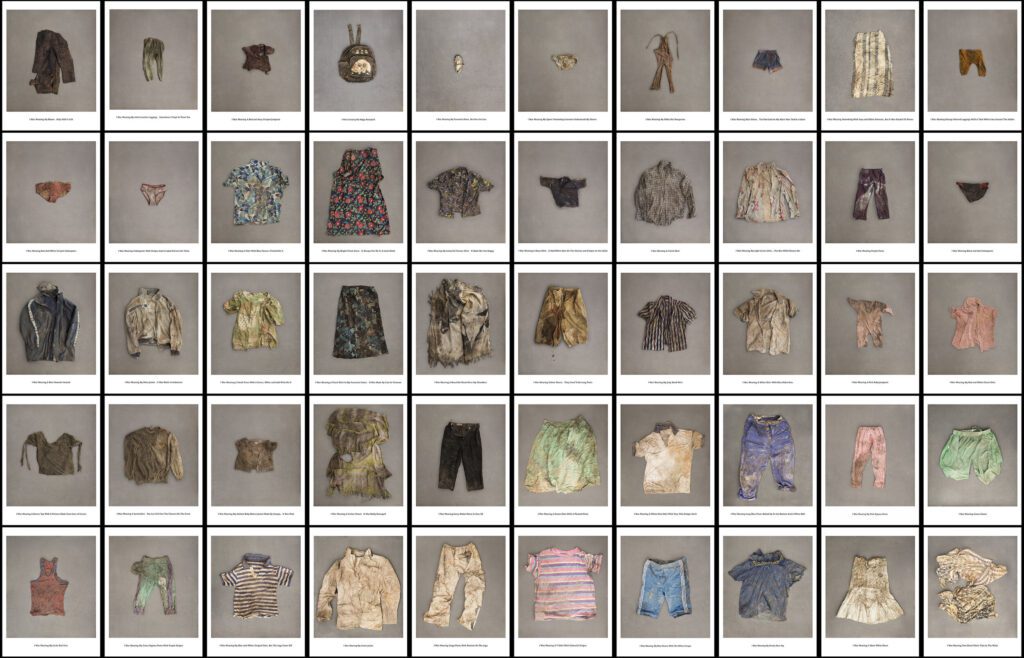

And what I did, was I started on this project where I took garments of clothing, laid them out one by one on the ground, cleaned them off, and tried to restore a semblance of humanity to these people, a little dignity to these people who had died in the most undignified way. But you can see, I think they eventually found 84,000 people’s remains in this mass grave, so if each person had on eight or nine garments, shoes, socks, underwear, pants, so there were hundreds and thousands of garments there, and I started shooting them, and the guys I was with who were supporting me were in tears, and I just, I just wanted to stop, but I felt like I had to, had to go through this. And so these are just some examples and you’ll see.

Each one has a text in the first person, and I think of them as portraits. I think of them as portraits of victims as opposed to still lives of objects, and the text in the first person is my way to try and let you feel like you’re looking at a person as well. So it says, “I was wearing my favorite shoes, but one got lost.” “I was wearing green underpants.”

So my question for you is, when you come across something like this, where do you start and where do you stop? You know, is that one picture of a shoe enough to tell the whole story? Because then I started feeling guilty that I wasn’t capturing every item of clothing, but I also was conscious of the emotional trauma it was having on the people who were supporting me. And I was reminded of the story that a survivor had told me a few days before, how she had survived by pretending to be dead, lying under a pile of bodies, and she heard the murderers, the perpetrators, say one to the other, “I just need one more and I’ll have one hundred.” And I just thought, if this woman could endure that, to hear humanity reduced to these crass numbers, and she could get through it and survive, I felt like I could stay present to make a hundred photographs as a tribute to her story.

So this project is a hundred portraits of victims of the genocide in Rwanda. The one on the top, “I was wearing my doggy backpack.” We can all imagine this child. None of us have any idea what a million dead people is like. I don’t even think we can imagine what a thousand dead people is like. But we can really, really imagine this little kid with a doggy backpack. He had friends, parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, just like us. And that’s what I really wanted to do, is humanize these people.

So, the last one you’ll see, it’s got nothing in the square because I felt like I couldn’t get to every item of clothing, and I wanted to sort of remind us that these issues are endless. And so the last one, instead of saying “I was wearing,” is just the plain gray square, and it says “We were.”

100 Days Improved

I want to share with you a short video that I posted on Instagram the first time this work was scheduled to be shown publicly. The exhibition shut down before it opened because of COVID. That was a couple of years ago. It is being shown in full in the Netherlands this year. Importantly for you to know, this year marks the 30th anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda. And I just want to show you this little video that I put together for Instagram on April 7th, 2020.

I was scheduled to open an exhibition to commemorate the anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda that got cancelled because of COVID. So I spent 100 days on Instagram posting a picture a day to commemorate the genocide in Rwanda. Here’s a look at what I posted.

And this is the 100 images, just a small contact sheet.

Namibia

So I want to move from Rwanda to Namibia, both genocides that occurred on the African continent. Namibia, the first genocide of the 20th century, 1904 to 1908. It was perpetrated by the then German colonialists of what was called Southwest Africa, and their intent was to eliminate the Herero and Nama population.

I’m going to show you these instead of showing you individual images. I’m going to show you a short video, but they are all still photographs. For those of you that don’t know, I just want to highlight the definition of the term genocide because we hear it a lot, but it has a very specific and definite legal definition. And it is this idea of mass killing with the explicit intention of eliminating a race, an ethnic group, or a group of people, but at the idea of the intention to completely eliminate a group. And that’s how it’s defined differently from crimes against humanity, from war crimes, from other colonial wars. And it is a very specific term, and I think it’s the idea of that intent that has made this really the most heinous crime against humanity. So these are some of the landscape works from Namibia. You’ll see some of the same kind of style that we’ve talked about earlier.

For the last decade, my art practice has dealt with the recurrence of genocide and specifically the public fatigue around the genocide narrative. Through that fatigue, I believe that we, society, have become complicit in enabling perpetrators of genocide to continue this ultimate crime against humanity. Through my work, I try and use the concept of filters and veils to look at specific sites where acts of genocide have been perpetrated. I’ve spent some time in Namibia where the first genocide of the 20th century happened, and that was between 1904 and 1908, where the then German occupiers of what was Southwest Africa attempted to completely annihilate the Herero and Nama populations. For the World Project, the landscapes from Namibia are large format abstract landscapes, and I tried very hard in these works to create aesthetic images as opposed to documenting the brutal facts. The reason for that is by creating these aesthetic images, I hope I create a space for you, the viewer, to interpret the images in your own way.

Bosnia: The Srebrenica Genocide

Okay, so from the beginning of the 20th century to the very end, 1995, where 8,000 Muslim boys and men were massacred with the world fully aware of what was going on. There are some extraordinary historians who’ve written about the history of genocide. Never once in the history of genocide has a Western government intervened in time to stop it. And with Bosnia specifically, they say it was the genocide that the world had the most knowledge of what was about to happen, and we still didn’t intervene. So what I was trying to do here was echo some of the images that I’ve done before.

I don’t really show my work in sort of modules of “this is the Holocaust,” “this is Namibia.” Like you’ll see if you come to the gallery, they’re all mixed up because really what I want to talk about is the common thread between them, which is us, which is humanity. But what I’ve tried to do in the pictures is shoot stylistically similar work at different places, so for me, this picture mirrors the one that I told you the story about with the man who saw his children being killed. They look very similar. You start to link these ideas through the work.

An interesting triptych I want to just point out something about my titles. So, this one in the middle is called “Eroding the Past,” this idea of sort of forgetting the past, and you’ll see the way I’ve shot it that almost like scratched up from the light, but it almost looks like the detail has been scratched up, we’ve eroded the past. And I know in some of your classes there’s a focus on context, concept, content, and I think about that a lot in my work. I try and use visual tools to reinforce the idea of what my photographs are trying to say.

Archival Glicée Print on Hahnemuhle Photo Rag

I just want to go back for a moment to the first triptych I showed you. So, look at this one, and then I’m going to go back to this one. Completely different stylistically, right? This is much more literal, it’s like step one, step two, step three. We can see the progression of chaos, much more didactic. I’m sort of telling you step one, step two, step three.

What happened in these ones ones is much more abstract, and I think, you know, as an artist, I was becoming more comfortable with the subject matter, and I was becoming more comfortable with how I was shooting it, with this idea of abstraction. In the beginning, I felt very constrained, like I was dealing with such heavy material that I couldn’t be sort of loose and free, and as I got more and more comfortable with the subject matter and with my treatment of it, you can see an interesting evolution in the works. These three are probably the most abstract works that you’ll see if you come to the gallery.

I’m an artist, I’m not a historian, I’m not a documentarian. I use this idea of witness distance very freely, very few of the pictures have documented the specific site where something happened. I told you, I’ll go to that site and then work out a way to stay within witness distance, and this is a great example. Nothing happened here, but the river that you see, it ends in a lake, but the water that fills that lake runs through the town of Srebrenica. So the idea is that the water witnessed and it ended up in the lake. So the idea is just the symbolism.

My titles are super important to me. I spend a lot, really a lot of time. I do a lot of research in literature. I take a lot of my titles from writing on the subject matter. This piece is called “The Quiet Valley,” and this one is called “The Quiet Valley Filled with Sound.”

A poppy field just outside of Srebrenica. For me, I think one of the more meaningful pictures because the poppy became the symbol of life and hope for the soldiers in the trenches during World War One. World War I was a terribly bleak war, a lot of the combat happened hand to hand, and in these muddy fields covered with death where the World War I took place, the poppy would spring up and there would be these pops of life and color. And when I saw this poppy field outside of Srebrenica, I really, really wanted to shoot it.

You can see my technique quite clearly here. You can see how I’ve moved the camera so you can see the mountain line in the background. As I move the camera, this darker line is that same line that I just shifted downwards by moving the camera.

In this one, for example, it’s much more blurred, right? So I’m moving the camera for the whole duration of the exposure. So for those of you who do photography, play with that technique a little bit. The shutter speeds are anywhere from a sixth of a second to 2 seconds, and if you keep your camera on the tripod and then move it for part of the exposure, you’ll start to get some really interesting effects of part of your image being sharp and part of them being blurred.

I love this one. It’s a very subtle image, but it shows my technique. So it’s some weeds basically just in a forest, and you can see up here, there’s this little piece of sky between these trees, but by dragging the camera, I’m dragging that column of light right through the image. So all those works we’ve already talked about today are this idea of bearing witness, the idea of the veil that I talked about. I move the camera to create this milkiness between you and the landscape. And then I started thinking much more about the process of healing and recovery because in fact, you know, we go through these horrendous moments in history and our lives go on, you know, we continue, we put the pieces together again.

Newest Works

So I started working through my archive to go back and look at some of the images I’d made in the past and started thinking a lot about this idea of healing and rebuilding. So I want to share with you now, just to finish off, my most recent works that I’ve made in the last year. I just debuted some of these at the Art Fair last week. So what I’ve done with these is take landscapes again within witness distance of sites of historical genocide from my archive.

So this image I made in Poland in 2015, but only last year I came up with this idea of how do we put the pieces together again to heal, and we do in fact heal. We experience loss, we experience sadness, we experience trauma, but we do put the pieces together again. But I was very interested in this idea of how we rebuild, but the pieces don’t fit together in exactly the same way. And that’s what these works are intended to do.

This is a really interesting example of the idea of bearing witness.

So these are the sand dunes in Namibia. Nothing happened on the sand dunes, but if you stand on the sand dunes, you look over the site of the first concentration camp that was ever established in modern history. So the title of this is “Witness and Sentinel,” but for me, it really talks beautifully and poetically to the idea of witness.

And then this one, I just want to tell you a little about it. For me, a really important picture. It is one of the rare cases where I’ve actually documented the specific site where something terrible happened. On this tree between 1904 and 1908, hundreds of Herero people were hanged by the German occupiers of Southwest Africa. And you know, 100 years later, 110 years later, I was there, and the Herero people had turned it into sacred hallowed ground. There’s a very simple little wooden fence around it so people don’t go and play on the tree or climb on the tree, and they would go there to pay respects to their ancestors who had perished in the genocide. And we went there, and everybody was incredibly respectful, and I took some photographs. And two months after I took the pictures, I got word that the tree had fallen down almost under the weight of time and the burden of memory. So this is a featured piece in my body of work. It’s the biggest piece I’ve ever made. It’s about 2 meters. It was really a tribute to the Herero people and their heritage.

A Few Lessons

So that’s all I wanted to show you. And just to summarize, I just want to share a few of the lessons again, remind you of the lessons that have been important to me, and if even one of them stays with you, I’ll be completely… The most important thing with photography is shooting the light. And you can see here that’s what makes this picture work is the way the light is hitting the tree. Someone once told me, if you’re going to shoot landscape photography, you only need two things: an alarm clock and a tripod. And it’s really about looking for the light. The word photography means drawing with light, that’s where the term comes from. And as you pick up a camera, look less for the subject and more for the light. If light’s hitting an ordinary subject in an interesting way, you’re going to get a beautiful photograph.

For me, I said the idea of referencing and researching is super important. I have a handful of academics and a handful of artists who’ve completely inspired my practice. I would never have come up with these ideas were it not for my research. So I really encourage you to look at artists whose work you admire, to understand what they’re doing. There’s an artist who I most admire, his name is Alfredo Jaar. He’s collected in every major museum around the world, and he’s incredibly research-driven in his practice. He also is one of the most highly sought-after teachers of graduate art school. Students line up for his classes, they’re always oversubscribed. And I was talking to him because he’d also worked in Rwanda, and he was telling me when he teaches art students for the entire semester, until the last two weeks, he does not let his students make anything, not a sketch, not a drawing, not a photograph, not a sculpture, nothing. All he’ll look at is their writing. And once their ideas have been more formalized and crystallized, then he’ll let them, in the last two weeks, go and try and make something. And I thought that was, for me, a really, really interesting approach. You’re all going to hate me if your teachers make you do this next semester, but it helps me a lot in my work.

We talked about the idea of coming up with something new, which is super hard. I’m not smart enough to do it, but think about new ways to approach subjects that people think they know. I know you’ve been taught a lot about this idea of integrating concept, content, context. For me, I never use a visual tool that doesn’t reinforce what I’m trying to say with the work. If there’s blur, there’s a reason that’s blur. If it’s black and white, there’s a reason it’s black and white. And I think it’s important for me to work with intent because I always look at an artist’s work and say, “What’s that artist trying to tell me?” And I try and work in the same way to put intent out there so that it asks the question of people looking at my work, “What is Barry trying to say with this?”

So on that note, the show opens tomorrow at Holden Luntz. We’re doing an artist talk in the morning, and it’ll be up for a month. So seeing the pictures in real life is very different from seeing them on a screen, so I hope a lot of you will make it to the gallery. I wanted to thank the gallery for giving me this amazing opportunity. I’m super, super happy to be here. And now I think we have like 15 or 20 minutes if anyone has any questions. Anything, anything, anything is fair game.