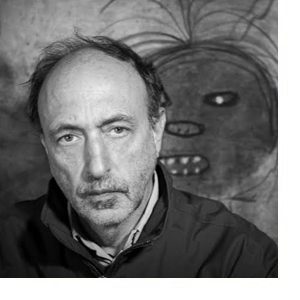

Roger Ballen is one of the most influential and distinctive voices in contemporary photography. Born in New York and based in South Africa since the 1980s, Ballen’s work has evolved from documentary roots to psychologically charged, surrealist tableaux that blur the lines between photography, drawing, and installation. Over a career spanning more than five decades, his visual language—now widely described as “Ballenesque”—has explored the subconscious, the absurd, and the unsettlingly beautiful.

In this wide-ranging conversation with Holden, Ballen reflects on his early photographic influences, the move from black and white to muted color, his rejection of traditional portraiture, and the complex psychological spaces he constructs in his imagery. What unfolds is a compelling look at an artist who is both deeply introspective and continually experimental—someone for whom photography is not just a tool, but a lifelong journey into the mind’s darker, more poetic terrain.

Luntz – You grew up in a household where photography was very much present. When did you decide to pick up the camera yourself, and do you recall what subjects you were interested in photographing in the very beginning?

Ballen – My first camera was a Brownie (Kodak) when I was five years old. I got another camera when I was around thirteen, but I was just playing around then. When I graduated from high school in 1968, my mother bought me my first serious camera: a Nikon FTN. I’ll never forget the first pictures that I took which were of a prison. In 1969 I went to the Woodstock Festival, where I took more photographs. On the festival’s 50th year anniversary, The New York Times asked me if I had any pictures of Woodstock. I looked at these three contact sheets – and I hadn’t really looked at those in fifty years – and I found many great pictures from the point of view of the festival. They did a four or five-page feature on the 50th anniversary. Upon reflection, taking these photographs was very important to the development of my photographic career. At 19, I saw that I was already able to take good pictures. Perhaps I had cultivated a photographic eye and passion through my mother’s friends: Henri Cartier-Bresson, André Kertész, Elliott Erwitt…Their photographs were all over my childhood house.

Luntz – Your move to South Africa was a turning point in your life. Could you please talk about how this came to be, and what were your initial experiences / observations like in terms of photography?

Ballen – The first time I got here (South Africa), I hitchhiked from Cairo to Cape Town. I worked on my first, published photo book called Boyhood. Afterwards I took a trip from Istanbul to New Guinea; a two-year trip across Asia. Subsequently, I went back to America and did a PhD in Geology. Then in 1982, I moved to South Africa permanently. Initially the works were more documentary, but I’m not really political. When people looked at my work, they always said the work had something to do with apartheid, and I said: ‘Not really.’ The inspiration for what I was doing in the 80s and the early 90s was like Samuel Beckett. I did a film called Ill Wind in 1972 in Berkeley, and it was about a man who is kind of an outsider walking around this area. So that same theme of the outsider has persisted in my work since the early 70s. It was an amalgamation of ‘vision’ and being more documentary, whereas now it wouldn’t be documentary in any way. Now it’s the documenting of the mind.

Luntz – Which artists, filmmakers, or photographers has influenced your work? How do you see your photography and filmmaking in reference to other artists active today, or figures you have regarded as important in the past?

Ballen – From a photographic perspective, the most influential figures for me have come from my mother’s era. Kertész taught me that photography could be art. Cartier-Bresson introduced the idea of the decisive moment. Elliott Erwitt showed me the role of humor in photography, and Paul Strand, the power of composition. They laid the groundwork for everything I do.

Everything accumulates, you see. I can look at a tree, or a lizard on the wall—and it’s the same experience as looking at a piece of art. Something to ponder, something to reflect on. These photographers formed the foundation, and ultimately, so did my study of nature. Geology was my profession for thirty years, and it, too, shaped how I think about the world and the purpose of life. These have been my major influences.

Luntz – Having shot in black and white for almost half a century, how did you transition into color photography – and, if it has, how did your approach towards the medium shift with this transition?

Ballen – I worked in black and white for fifty years. So, when I created the Ballenesque book, I decided to also make a film to accompany it. I had previously made several music videos with the band Die Antwoord, and many people became interested in how I approached those projects.

At the time, I was using a Rolleiflex 6×6 film camera, but I reached out to Leica—and they provided me with a digital camera that could also shoot video. Then, just by chance, I took some color photographs. Initially, I thought I’d just convert them to black and white. But to my surprise, in some cases, the color versions were actually better. I couldn’t believe it—I had never had any real interest in color photography.

Still, I decided to explore it a bit further. The color images felt different: they were inspiring, challenging, and brought something new to my work. I also began to appreciate the advantages of digital over film. Film was hard to find, the developing, the contact sheets…etc. Switching to digital helped my photography in many ways. I didn’t feel nostalgic about leaving film behind—fifty years was enough (laughs).

People often say that color is more abstract, while black and white is more purist and formal. Color reflects how we see the world—like light itself.

The transition wasn’t difficult for me. I already had a strong understanding of color tonality, so there was no real learning curve. It felt completely natural—like drifting smoothly down a river.

Luntz – Was it a conscious decision to use ‘muted’ colors when you started photographing in color? What kind of an effect do you think the use monochromatic colors has had on the way the works are perceived?

Ballen – I think it fits naturally with my aesthetic. The transition from black and white to color was, in some ways, easier because the colors I use are all quite muted. They align with the tone and atmosphere of the environments I work in.

These are dark spaces—dimly lit, unpolished, not glamorous. They’re rough, raw, and carry a certain edge. You walk into scenes of chaos and breakdown, places that feel unsettled. So naturally, you wouldn’t expect bright, vibrant colors in these settings.

This is the world I’ve created.

Luntz – Could you speak about your focus on abandoning people altogether in your practice and its relation to the surrealist aspect of the works?

Ballen – Up until around 2001 or 2002, nearly all my photographs featured people’s faces. Then, beginning in 2002, I entered what I call the “intermittent period,” where the work shifted more toward portraiture and drawings. By 2004, faces had largely disappeared from my images.

I think I wanted to explore new directions because I felt confined by focusing so heavily on faces. When a photograph includes a face, people tend to judge the entire image based on that face. But for me, the drawings—and the animals, which I consider the next most expressive subject after faces—were becoming more important.

I felt there were other elements of the aesthetic that needed space to emerge. Faces had started to limit what I was trying to express, so I chose to move away from them.

Luntz – At what point did you decide to incorporate other mediums such as drawing and painting into your works? Did you think this was necessary to heighten the fantastical element?

Ballen – The drawings first emerged from spending time in people’s homes during the 1990s. Between 1995 and 2000, you can see drawings appear in my work in a semi-documentary way—they were simply part of the environment I was photographing.

But by 2004, that changed. I began asking people to draw, or I would create drawings myself directly on the walls. These drawings became an integral part of the subject matter within the images.

Since around 2002, drawings have played a significant role in shaping what I now refer to as the Ballenesque aesthetic.

Luntz – What are the characteristics of a Ballenesque photograph?

Ballen – While it’s true that the Ballenesque aesthetic resists a strict definition, there are certain key elements that often characterize my work. A Ballenesque photograph typically conveys a psychologically charged atmosphere with surreal compositions and an underlying sense of visual tension. The settings are usually confined, windowless spaces that feel detached from the outside world, serving as visual embodiments of the subconscious mind. Human subjects—often individuals living on the margins of society—frequently confront the viewer with a gaze that feels both intimate and inaccessible, evoking a complex emotional response. These environments are populated with seemingly random objects, animals, and hand-drawn marks that create a sense of disjunction, reflecting the irrational and unpredictable nature of dreams. The juxtaposition of human, animal, and inanimate elements disrupts conventional boundaries, fostering an atmosphere of absurdity and unpredictability. Despite this apparent chaos, each photograph is grounded in a strong sense of formal composition, with an emphasis on visual harmony and the careful integration of shapes and lines. Ultimately, the Ballenesque aesthetic seeks to explore the complexities of the human psyche through a visual language that is both unsettling and compelling.

Luntz – What do the drawings on the walls mean? As we look through the photographs, we slowly realize that they are stylistically similar almost like primal cave paintings, yet there is also an unsettling feeling as if they are visions of paranormal creatures flowing through these physical spaces.

Ballen – I think they are about the enigmatic world. They are not one thing or the other. It’s about a kind of spirit world—something intangible. When I represented South Africa at the Venice Biennale, I created a project called The Theatre of Apparitions, which carried an underlying sense of otherworldliness.

What do these drawings mean? Honestly, I don’t know. I can’t say exactly what they mean—they’re just there. It’s like looking at the wall behind you—what’s really there? Maybe there are spirits floating in the air. It’s about making the invisible visible. That’s all.

From a formalistic perspective, one thing that’s very important is how drawing integrates into the overall aesthetic. If you were to draw something in one of my pictures, the way you draw would probably not work in my photographs. You couldn’t just place a Picasso-style drawing on the wall—it wouldn’t work.

If I handed you a pen and asked you to make a drawing, my next question would be: What are you going to do next? If I make a drawing and put it on the wall, the real challenge is: What comes after that? How do I create a photograph that will genuinely move people?

Luntz – Many would consider your photography dark and disturbing, perhaps conveying a feeling of restlessness even, yet you’ve talked about them being absurd. Why is it important for your work to challenge the viewer? What would you want your audience to take away from your work?

Ballen – I’m only challenging myself. I’m not taking pictures deliberately for the viewer. I don’t know anybody’s state of mind. I’m there to create pictures that challenge me—and hopefully other people. If they don’t challenge anybody, well, then it’s a bit depressing as an artist. If the pictures don’t have an effect on people, then what am I doing?

They call the works dark; I’m glad they have that effect. Then I’m successful. It means the viewers are reaching a part of themselves that they can’t deal with, that they’ve repressed. If they said, “Oh, that would go nicely on my wall above my new bed!”—then I’m not being successful.

The pictures are dark because you can’t deal with certain sides of yourself and the world around you. So, the pictures are un-repressing you. They’re challenging your status quo, which is what art should be doing. Most art isn’t doing this. It’s mostly decorative, or sometimes political, but it’s not challenging people’s psychological state.

Luntz – Do you see these pictures as humorous? Humor is psychologically often based on a sense of violation – or at least social and personal limits being challenged or disregarded. Do you intend the photographs to be perceived as humorous, escapist or threatening?

Ballen – I think most of my pictures are humorous; they’re absurd. I enjoy taking these pictures. I never get depressed. I think they’re funny, and this has been my aesthetic for the last thirty years. They might be dark, but they are also funny. It’s dark humor. Humor also changes from society to society. What’s funny in one place might not necessarily be funny in another.

Luntz – In your book, Spirits and Spaces, you say that the spaces in your photographs are not just physical– “they are manifestations of deeper recesses of the mind”. Could you please elaborate?

Ballen – A space is not necessarily a dimension; it’s also a state of perception. Just because there’s a wall doesn’t mean it’s a space—it’s also about how the space feels. Or think about going from a waking state to a dream state. These are more poetic, philosophical ways of describing cognition and perception. What we see in the picture is a space of the mind. It’s about a mental space.

Luntz – The physical spaces in the works appear to be chaotic and clustered yet there is also a certain pattern throughout the series. What is your preparation process like prior to a shoot, and what underlying metaphors are there regarding this chaos – order duality?

Ballen – I never think about anything before I get there. I don’t plan anything—like the mind. I can’t plan how I’m going to sleep tonight. How would I do that? Most of what you see in art and photography is planned, contrived. In my pictures, you might feel a sense of chaos, but there’s also a very strong formalistic element. There’s a lot that goes into each detail, but the content exists in a state of chaos, mental disorientation.

The installations are usually created in three to four days. But even if you create the set, you still don’t have a photograph. It just means you’ve made an installation, a setup. That’s where the trick is.

Let’s say I’m taking a picture of a baby blowing out the candles. Then I have to put candles on the cake, and maybe the baby gets near the candles, starts crying, and doesn’t want to do it. So then, I don’t have a photograph. This is also very difficult because the question is: What’s appropriate in that photograph? Is it appropriate to bring a dog near the cake and have it eat it? Is it now appropriate to take the candles out and have the mother sit there, cut the cake, and cry? Not only is the content important, but the visual elements must be as well.

It took me thirty-five years of work to reach this level. There has to be something in the picture that you couldn’t have imagined.

Luntz – What has your approach to photography taught you about your own psyche and inner self?

Ballen – I feel privileged because I didn’t start photography until my late teens or early twenties. I was interested in psychology and philosophy, so in many ways, I have a very existential sense of self. I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of finding the self and journeying through the world and the mind. This has always been part of my personality.

You also have to realize that I have a scientific mind as well. All of these influences have helped. I see myself as both a scientist and an artist. Photography is simply another tool to understand this enigma we call life. These tools help piece together the puzzle, but as you get older, you realize you’re not really “getting there.” You think you will when you’re young, but you don’t. All you can do is ask yourself good questions and feel like you’re capable of formulating answers (which may lead to more questions). And there’s nothing wrong with that.

Luntz – Let’s talk about the museum you have built. What was the purpose behind it, and how was the museum realized?

Ballen – The museum is called the Inside Out Center for the Arts. Its purpose is fourfold: first, to showcase work related to Africa; second, to present something with a psychological impact; third, to represent my aesthetic; and fourth, to offer something engaging for the community and visitors in general.

The first exhibition, titled End of the Game, is still ongoing. It’s a historical, cultural, and psychological exhibition, speaking to the viewer on multiple levels.

Luntz – Why the name ‘Inside Out’?

Ballen – Initially, it was going to be called the Roger Ballen Center for Photography. However, since much of my work extends beyond photography—into installations and videos—I began to think it should reflect contemporary art. But there are already a million museums with those names.

My work is fundamentally psychological; it’s about the interior and finding the experience through the inner world—the non-verbal, archetypal realm. It’s the silent mind. I felt that the title Inside Out captured this concept to some degree.

Luntz – Do you have an idea about what you’d like to do in the future? Is there anything you’d like to say that hasn’t been said through your photographs? Where do you see your practice going from here?

Ballen – You can’t predict the future. Each year that passes, you try to dive a bit deeper—that’s all there is to say. I do plan to make videos based on the Spirits and Spaces book, and I’m working on a video about Dante’s Inferno. I enjoy combining photography with video, and when I have the opportunity, I try to create installations.

If you look at my photographs, there’s a significant act of creating installations behind them. In a way, the installation comes before the photograph. The installation is made with the intention of creating a photograph. I’m not like an ordinary artist who makes an installation simply for the sake of the installation. These installations are crafted to enable me to complete the photograph.

I’ve seen many artists over the past twenty years who create installations and then photograph them. But if you put that photograph on the wall, it doesn’t have the same impact. It’s very challenging to make an installation and then photograph it in a way that feels real or has a psychological effect.

One of the most influential and important photographic artists of the 21st century, Roger Ballen’s photographs span over forty years. His strange and extreme works confront the viewer and challenge them to come with him on a journey into their own minds as he explores the deeper recesses of his own.

Roger Ballen was born in New York in 1950 but for nearly 40 years he has lived and worked in South Africa. His work as a geologist took him out into the countryside and led him to take up his camera and explore the hidden world of small South African towns. At first he explored the empty streets in the glare of the midday sun but, once he had made the step of knocking on people’s doors, he discovered a world inside these houses which was to have a profound effect on his work. These interiors with their distinctive collections of objects and the occupants within these closed worlds took his unique vision on a path from social critique to the creation of metaphors for the inner mind. After 1994 he no longer looked to the countryside for his subject matter finding it closer to home in Johannesburg.

Over the past thirty five years his distinctive style of photography has evolved using a simple square format in stark and beautiful black and white. In the earlier works in the exhibition his connection to the tradition of documentary photography is clear but through the 1990s he developed a style he describes as ‘documentary fiction’.

In his artistic practice Ballen has increasingly been won over by the possibilities of integrating photography and drawing. He has expanded his repertoire and extended his visual language. By integrating drawing into his photographic and video works, the artist has not only made a lasting contribution to the field of art, but equally has made a powerful commentary about the human condition and its creative potential.

His contribution has not been limited to stills photography and Ballen has been the creator of a number of acclaimed and exhibited short films that dovetail with his photographic series’.