Discover the captivating journey of Melvin Sokolsky, from his childhood fascination with composition to his groundbreaking fashion photography. Sokolsky’s interview unveils the inspirations behind his iconic bubble and fly series, shedding light on his creative process and vision. Dive into his narrative, where imagination meets reality, and explore the timeless allure of his photographs, inviting you to experience the joy and meaning within each image.

Luntz – What was your introduction to photography? How did you become involved in such major fashion campaigns?

Sokolsky – When I was a little kid, about seven or eight years old, I would sit at the kitchen table watching my mother cook at the stove across the room. To the left of me on the table, was a salt and pepper shaker nestled next to an artificial bouquet of flowers. If my mother moved at the stove and was obscured by the bouquet of flowers, I suddenly had a strong urge to move because it made me uncomfortable, not being in control of the composition before me. In other words, I liked to see the world from a point of view that made me comfortable.

At that time in my life, I didn’t realize that I was most content seeing reality as if I was looking through a camera. I believe photography is deciding where to put the camera; because the result is satisfying and excites you.

Sokolsky – Do you know the Irving Penn pictures? Where he puts people into corners?

Luntz – Like the Truman Capote portrait?

Sokolsky – Irving Penn created a corner, constructed of studio flats. In many cases, he would place a central object like a rug bundled up to seat his subjects. If you have studied his work, the corner is Irving Penn’s signature space.

In my view, the reason for corner flats is to contain the subject and capture their physicality. A kind of open barrier the sitter cannot escape. Penn then lets the sitter move around until they reveal the spirit of who they are in terms of how they gesture.

Luntz – I do see them, as they are sort of in uncomfortable positions.

Sokolsky – How one adjusts from an uncomfortable position reveals the spirit of the sitter. I believe he is looking for the inner clock of the sitter. Penn explores the spirit of who the person is via gesture. When people ask me who is your favorite photographer? Penn has an original vision that stays with me. If I go walking along the street and I see somebody in a corner doorway, Penn pops into my mind.

Luntz – I read that a Hieronymus Bosch’s painting, The Garden of Earthly Delights, inspired your work.

Sokolsky – Yes! When I first saw the painting, I was overwhelmed by its inventiveness.The Garden of Earthly Delights is a painting that I couldn’t get out of my mind. My dad and I were in a bookstore, where I found a small book of Hieronymus Bosch’s work and took it to the checkout counter. The man that was checking us out asked: “You sure he should have that?” and my father looked at the contents, smiled, and said: “Sure he can have it.”

In that painting, there is a plant that looks like a bubble growing out of the water. When you view that detail in the painting, it is obvious my bubble images do not resemble the Bosch detail. Best said the painting was the inspiration for the bubble series. Many have asked why did you put a ring around your bubble images for Harper’s Bazaar?

I jokingly say that the rings of the bubble are the engine that power the bubbles!In my imagination, when I built the bubble for the Bazaar shoot, I secretly saw it as a Sokolsky aircraft that could fly anywhere on an engine built into of the rings that contain the bubble hemispheres. It was not a girl captured in a bubble. It was a woman at the helm of her spaceship.

When Einstein said, gravity bends, they thought he was amiss. Recently it was discovered that gravity does bend. My vision is about complying to mother nature, because nature has decided everything about us and what will happen to us. It determines how a flower grows; it decides what the weather is going to be. “Whether you believe in global warming or not.”

Luntz – I also had heard this story that you saw something like bubbles in a department store window display, and that perhaps also inspired you?

Sokolsky – The Christmas display of miniature bubbles in the department store was source information for building the bubble, not an inspiration.

The inspiration came from an advertising agency, Doyle Dane & Bernbach. I was about 19-20 years old. I went up to the agency, and a guy there said to me: “I like your pictures come back, I’ll give you something to do.” I said, OK. I came back a few weeks later, and he reached under his desk and threw me a coat with a fur collar, and he said: “Surprise me.” “You get $150 for a picture. If it’s any good, I’ll give you name credit.” When I delivered the photo, he said. “Wow. That’s wonderful.” And to my surprise! I got a name credit, Mel Sokolsky.” The ad ran in Harper’s Bazaar. A few weeks later. I got a phone call from a guy with an Austrian-like accent. “Hello, my name is Henry Wolf, I’m the new art director at Harper’s Bazaar, I saw your picture, and I thought it was neat,” and I said to myself that’s my brother Stanley screwing with me, so I hung up the phone. The phone rings again, he says: “I think we’ve been disconnected” and then I realized it was real. Henry Wolf gave me a couple of pages to shoot, and a cover try; I didn’t get the cover, but he did like the pictures, and he said, “You’re stronger than I thought you would be. How would you like to become a permanent fixture here?” So, I said, “wow, are you serious!?” In a moment, I became a Harper’s Bazaar photographer.

Luntz – So, after the fur coat?

Sokolsky – Yes, from an ad with the fur coat. OK, next thing, so you’re a Harper’s Bazaar photographer. At that time, Richard Avedon was the leading photographer of the Bazaar, taking classic high society pictures. I was new at the magazine and considered the kid. Trying to create a signature vision, I decided to shoot women showing emotion in places where the privileged class would never frequent, for example, against peeling walls in old tenements.Bazaar management decided to reject my pictures, their reasons: “Subscribers that read the Bazaar would not recognize the places where you’re putting our fashions.” Trying to encourage them, I suggested they think of my picture’s backgrounds as impressionistic textures. The person that saved me was fashion editor Diana Vreeland. Diana said my pictures were like impressionistic paintings and coaxed them to run a few pages. When the pictures ran, many subscribers wrote letters, “Who is this new photographer? “Finally, I found an audience.”

Luntz – Yeah, I would say you helped change how we perceive fashion photography.

Sokolsky – I saw my bubble pictures in Paris as if the girl in the bubble was in a spacecraft visiting and mingling with townspeople around and in Paris. The reactions from passerby was a natural emotion. There was no direction on my part. The people in the shot were actual townspeople going about their business, except for the fact of how the presence of the bubble stimulated them.

After the shoot, I was told Avedon had said that I would never get the bubble off the ground. When I arrived in Paris, I had to promise management that if things didn’t work out, I would shoot in the studio.

Luntz – Do you know what made you want to shoot outside? Were you a studio photographer in the beginning?

Sokolsky – Technically, it is easier to shoot the bubble outside in daylight. One must realize the bubble is a reflective sphere that reflects all of its surroundings. The light in Paris in February is beautifully overcast, making for an ideal situation for shooting. One must notice I used no lights because lights would create unsightly reflections in the sphere.

I’m in Paris, and I’m doing the Paris collections, and I wanted to give the audience a taste of the city. Most importantly, I didn’t want to shoot usual iconic images such as the Eiffel Tower. I didn’t want my pictures to look like an advertisement for a Paris travel brochure. I wanted to shoot Paris in a more intimate personal way.

I saw the shoot as a narrative, with a beginning, a middle, and an end, starting with the cover of the March 63′ Harper’s Bazaar. In that cover, we are looking from across the river towards New York; you see the Empire State Building in the background.

The bubble then lands in Paris floating on the Seine. It’s a narrative story taking us through different parts of Paris and the people who live in the adjacent small towns, ending at night at Pont Alexandre III.

You mentioned me seeing a bubble in a department store Christmas window. I noticed a small cluster of bubbles in a department store window. They were about 12 inches in diameter; they had plexiglass bubbles displaying shoes and handbags. I went into this store, and asked the window dresser, where he had the bubbles made. He gave me the name of the fabricator on Long Island. I went to the fabricator with a drawing of the bubble, two hemispheres six feet high cost $2,500.00 each back in 1963. I had two hemispheres fabricated. Then I had the rings made and bolted each ring to a hemisphere and hinged them at the top. Between the two rings, I had an 1/8″ aircraft cable. My studio manager Eli was uneasy about putting a model in the bubble and hanging it from a thin cable. I had him rent a small crane, the kind that puts signs up around the neighborhood. I attached the 1/8″ cable around the bumper of an old car and had the crane operator lift the car. The crane lifted the car effortlessly, I then asked Eli: “How much does Simone weigh?” he said: “about 120lbs,” “how much does the bubble weigh, maybe 80-90lbs,” so I said: “I’m sure it can pick up 200lbs, the aircraft cable has a test guarantee of 8500 lbs. So, if they can trust it on airplanes, why are you afraid that this is going to break?” He says: “It looks so thin, hard to believe. So how is she going to get out?” I said: “Eli, on the bottom, we will have another hinge and a pin with a retraction ball at the tip. You pull out the pin attached to a fine cable, and the hinge comes apart”. I was mechanically inclined all of my life as if I did all these things in another life.

Luntz – Wow, it took some engineering to make that happen.

Sokolsky – I don’t even know how to explain my insights. I was not an engineer.

Luntz – The Victoria and Albert museum has your Seine bubble picture and named it the most iconic fashion image in the last hundred years.

Sokolsky – Yes, the Victoria and Albert Museum gave me a special tribute. A poster featuring the Bubble on Seine image; V&A 100 years of fashion. I’ll send you the poster. The museum put together a traveling show of their collection of 100 years of fashion images. The show went to Australia, where the curators chose the bubble on the Seine as the most iconic fashion image in 100 years.

Luntz – I wanted to ask, your photographs are considered so iconic, which makes you a form of inspiration for fashion photographers today. Who would you say were some of your biggest influences in fashion or fashion photography in general?

Sokolsky – I liked Irving Penn’s pictures because he created images that were what I considered his signature palette. In both design and lighting.

Luntz – Would you say maybe Irving Penn is one of your biggest influences?

Sokolsky – I would say I have great respect for Penn, but I do not believe he influenced me. I do have great respect for his personal vision. My biggest influence is painters.Painters create pallets and ideas that are distinctive. If you look at Van Gogh, it’s an entirely different palette from Renoir. I want my pictures to reflect my ideas and lighting. To be so unique so as to when you say Sokolsky, the images come to mind that could only have been shot by me.

Luntz – Yeah of course.

Sokolsky – Today, we have the iPhone, that same palette for everyone.The iPhone is a wonderful tool. If it’s not being handled by somebody that has a vision, the iPhone is just capturing a banal image. If somebody has a vision, one could do a Paris collection on an iPhone; I would create a signature palette for my iPhone in Photoshop.

Luntz – How were your images received when they first came out? I remember you told me an anecdote last time we spoke that you overheard someone who was looking at your bubble on the Seine picture saying: “this guy is really good at photoshop but how?” and I figure that’s how people understand images that use illusion like yours in today’s world.

Sokolsky – Yes. Well, if you’re looking at this picture of a bubble, the girl on the bubble, and you don’t believe that it’s shot live, you figure that the guy put it into photoshop because photoshop is a wonderful tool.

Luntz – Because now we know photoshop exists, but back in 1963, how did people react to your images?

Sokolsky – At first, people thought they were wonderful, and then you had people that were saying, “What will he do to top them the next time?” History made them more iconic as time went on, as they had more exposure in museums internationally.

Luntz – Your pictures do feel very organic; there’s a notion in your photos of the weight, of the physicality of the model, of the bubble; there’s a sense of reality.

Sokolsky – Well, I want them to live in a space that’s not quite real but interesting to me. I’ve created imaginary spaces all throughout my career. I build my sets to mirror worlds that I have imagined. When the space and the model somehow balance, we see the surreal as reality.

LUntz – I wanted to ask you, you made the bubble series in 63,’ and then you made the fly series in 65′, what was the difference between those? Do you think that your bubble series inspired the fly series? Did you want to take it further?

Sokolsky – When I think about my life as a photographer, the most important desire I have is to create images that give the viewer feelings of hope and joy. I want the viewer to look at my pictures and feel good. Think of waking up and looking at one of my pictures, and it starts you off for a great day. I thought the Fly series would give one good feeling and also be unique if I could pull off the vision I had in my mind eye.

Luntz – I had a question regarding Martin Munkacsi for you, but I can ask you after you finish.

Sokolsky – I answered an advert in the newspaper about sharing a studio in New York City. I was with my girlfriend at the time; we were both around twenty. It was an old building on fourth avenue in lower Manhattan. We were let in by a man with a thick European accent. He introduced himself to us, Martin Munkcasi. His name did not register as an important photographer. He was immediately interested in my girlfriend, who was quite beautiful and a model. He told me to look around to see if the space worked for me. He then asked if he could photograph my girlfriend. Thinking he was a dirty old man, I said: “Why don’t you ask her.”

He proceeded to photograph my girlfriend as I looked around the studio. Piles of matted photographs leaned against the walls all around the room. I was shocked to find every picture struck me as great. I called out to Munkacsi. “Are these your pictures?” He shouted back at me.“Why would I have someone else’s pictures in my studio?” I was truly impressed.We came back a few days later to see the results of my girlfriend’s photos. They were shot on an 8×10 camera. The images were quite beautiful. Munkacsi looked at me and said. “Something is bothering you?” I smiled and said. “Nice, but why didn’t get closer to her” He smiled and said. “I didn’t want to distort her pretty nose.” He then picked up a scissor and cut the 8×10 chrome to a 4×5, her head filling the frame, smiled, and said: “You like this better?” A great lesson I will never forget.

Luntz – How were you able to combine your particular artistic aspirations with what Harper’s Bazaar wanted from you?

Sokolsky – I had a lot of problems at the Bazaar, but I also had some people that supported me. Some of the issues I had were, they thought the pictures were too weird. Let me give you an example; I did a whole series of pictures on the subway in New York. They wouldn’t run them.

Luntz – Why is that?

Sokolsky – Because management did not see their subscribers riding the subway.

Luntz – So, you had to struggle with that?

Sokolsky – It was touch and go as I did have support from Diana Vreeland and Henry Wolf. It all changed for the better after I shot the Bubble pictures.

OK, but all of a sudden, many letters came in and asked, who is this wonderful new photographer? It’s refreshing seeing new pictures with new ideas. Melvin goes from the guy you wanted to fire to “we better keep him because the subscribers love it.” It’s all about money.

All I’m saying is that there are certain human needs, and those human needs have to be met. When you’re a photographer, there are visual needs that have to be achieved based on how you feel and think and see, and if you meet them on a level that satisfies you, it appeals to you, and it gets a following, you become successful. If you don’t, you lose that success.

Luntz – Historically, the faces of fashion brands were its designers. You could say that it was the iconic designers who represented fashion brands, do you think it’s still the same today? Does fashion photography reflect the culture of what is happening at the moment?

Sokolsky – It’s supposed to. The internet watered a lot of that down.

Luntz – What do you think will be future innovations? What do you think will be in the future for fashion photography?

Sokolsky – It’s like asking me if there is a moose on the moon.

Luntz – You wouldn’t have any opinion?

Sokolsky – No, no, you can’t predict the future. I believe time heals everything. Museums see something special in vintage images. The price at galleries increases. An image that sold for a few thousand dollars now sells for hundreds of thousands. Most important to me is the images give great feelings to the viewer.

Luntz – If you had a special power to do anything, what would that be?

Sokolsky – I would like to be invisible whenever I want to be and have an invisible camera with me.

Luntz –Wow, why that in particular?

Sokolsky – If I could make myself invisible with an invisible camera. I could go anywhere and see the truth. I would not need to see the world as it is being fed to me via the internet and the news. I believe facts are facts. There are great sources of news which are being politically distorted. The invisible Melvin Sokolsky can seek and observe the truth. Most importantly, if you don’t put in the work and you don’t have the imagination, you’re not going to happen. People get angry at me when I say it. There’s no app, there’s no tool, there’s no anything. Tools have no brains; tools have no ideas. Tools are for someone that has an idea.

Luntz – Let me ask you then, how was it working with a production team? Because when I read the Paris book, it said that you had the model, you had everybody that was involved, and it was probably a team of 5-7 people maybe more.

Sokolsky – My studio was like a Renaissance studio of the past. We built everything from the raw material to the finished product. We built the sets in house; Painted and decorated, developed, and printed the images, the client got the finished product. The studio was made up of people I trained

.

If you tried to do the Paris 1963 bubble shoot, it would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars today; not to mention the exorbitant cost of the insurance. We shipped all of the bubble elements and my studio crew Paris.

Luntz – Would you say the model is part of the crew? How important is the model for the shoot? How meaningful is the relationship between the photographer and the models?

Sokolsky – The model’s talent is most important. I tested models in the bubble to see who was most comfortable high off the ground. Simone was most comfortable in the bubble as if she was the pilot of a spaceship.

Luntz – I read in your book that you had a very good relationship with her (Simone) that you guys could understand each other just by using gestures.

Sokolsky – Yes, in other words, we had shot a lot of stuff together; we were friends. After a while, we had a shorthand of my gestures to communicate how she posed, which was helpful when she was in the bubble. I had no personal relationship with Simone; in fact, she was friendly with my wife. Some distance with the model makes for a dynamic of more rewarding possibilities.

Luntz – How about the flying pictures with Dorothea McGowan?

Sokolsky – I asked Dorothea if she would do the Flying picture for the 1965 Paris collections, and she said OK. I fitted her in the rig, and the tests were great. Then a week before we were supposed to go to Paris, her father passed. For a few days, we were in limbo. After much thought, she decided to do the shoot. When I look at some of the pictures today. I find Dorothea to be so special in the Flying pictures in terms of gesture; it makes me want to cry.

Luntz – I wanted to ask you to finish off, however, we can keep talking, you’ve won a Lucy award, you’ve won significant tv commercials, you have the bubble, and the fly pictures as iconic fashion photographs. What could you gather from your career, what could be next? Or how do you think you’ll be seen in the future?

Sokolsky – After much thought, I realize all of the awards and prizes are not as rewarding as you may think. Most important to me is for people who see my photographs is for them to experience the joy and meaning the image expresses. I would like my photographs to be “Eye Music.”

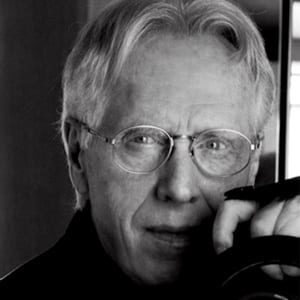

Born and raised in New York City, Melvin Sokolsky was never formally trained as a photographer; instead, he learned the art of photography through a trial and error approach at a young age using his father’s box camera and relied on conversations with advertising photographers for his mentorship. His photographs of internationally famous personalities have appeared in many of the major museums and magazines worldwide. Sokolsky’s photograph, Bubble on the Seine, depicting a model inside one of his iconic bubbles, was named one of the 100 most influential fashion photographs of the 20th-century by the Victoria & Albert Museum.